Plain Talk 2Pre-Contact

Chapter 1Pre-Contact

First Nations peoples are the original inhabitants of most of the land now called Canada. First Nations people prefer the name First Nations when referring to the collective. Individual Nations are defined by their own languages, cultural, and spiritual traditions rather than criteria developed or established by settler governments or academics.

Section 1

Original Inhabitants

of the Land

First Nations people have been on this land since “time immemorial.” Academics in the Western traditions have theorized that Indigenous people migrated to North America in several waves from northeastern Asia via Siberia and the Bering Strait between 40,000 and 70,000 years ago, and again about 25,000 years ago. Archeological evidence suggests that Indigenous settlement of North America may also have occurred over the Pacific Ocean, by boat from Asia and the Pacific Islands.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

By the time Europeans appeared in Canada, the population of First Nations numbered in the millions, living and prospering from coast to coast to coast, with a variety of social, economic, political, spiritual and cultural systems and practices. The appearance and presence of Europeans is generally referred to as the time of “contact.”

This Plain Talk provides a description of First Nations in Canada prior to colonization and occupation by Europeans, primarily by the English and French in the 1500s. In fact, contact with Europeans may have started around 1000 CE when the Vikings founded the colony of what is now known as L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. After 1500, English and French persisted in the colonization of modern day Canada, resulting in a profound impact on cultural, economic and military influence of First Nations peoples.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

First Nations inhabited and controlled their own regions and territories of what was to become Canada, or what the Anishinaabe and many other nations named Turtle Island, which refers to all of North America, developing sophisticated and intricate ways of living and thriving in their environments and on their lands. The vast country has distinct geographical differences, which had an influence on the cultural customs and practices of the resident First Nations. For convenience, it is possible to identify some groupings of First Nations, each group associated with geographical characteristics and sharing some cultural similarities, although this is by no means exhaustive:

Section 2

Histories, Cultures and Languages

First Nations people inhabited the land which we know as North American long before the European settlers arrived. From the relationship that First Nation people have with the land, to ceremonies such as the potlach and sweat lodge, First Nations people thrived in their cultures, identities and economies long before contact with Europeans.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Relationship to the Land

First Nations have always had a strong relationship with the land and with nature. First Nations relationships with the land were entirely different from that of the future settlers and colonizers. First Nations people do not consider land to be something that can be bought, sold or traded.

Connection with the traditional lands is fundamental to the cultures, identities and economies of First Nations peoples. The land provided shelter and subsistence, and First Nations

showed the land and its wildlife enormous respect. When an animal was killed for food, a prayer was made to the Creator, thanking the spirit of the animal for giving its body so that people could live. Hunters took only what was necessary to survive. Every part of the animal was used. Clothing was made from deer hide and decorated with feathers and porcupine quills. Bone was crafted into tools and jewelry. First Nations have always seen themselves as part of the natural world, in a symbiotic relationship with the natural world.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Elders

Elders are community members who have the respect of the people because of their wisdom and knowledge of traditional customs, language and culture, regardless of age or gender. Elders earned this status through their dedication, experience, and understanding of the need to strive for balance and harmony with all living things.

Talking Circles

Talking circles are a striking example of First Nations respect for others. Individuals in a group of people, often sitting in a circle, were given an opportunity to talk about their opinions and feelings without being interrupted. The person talking held an object like a feather, and it was understood by the group that the person speaking should be listened to with courtesy and concern. When the speaker passed the object to another person in the group, it was a signal for that other person to express their thoughts and ideas.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Sacred Medicines

Sweetgrass, sage, cedar and tobacco are sacred plants that have traditional healing, ceremonial and spiritual meanings and applications. These sacred medicines are used individually or can be mixed together and burned. In a process called smudging, medicines are burned to produce smoke that cleanses and purifies the mind, body, and spirit.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Potlatch

The potlatch is an important ceremony in the culture of many Pacific Northwest First Nations. The host family of a potlatch would give away much of its accumulated wealth and materials goods as a gesture of goodwill, and to demonstrate social status. Events like singing, dancing and spiritual ceremonies could take place during a potlatch.

Sweat Lodge Ceremonies

Sweat Lodges, usually dome-shaped and round structures, are a place for spiritual, mental and physical renewal. People enter a Sweat Lodge according to certain rituals and customs. Inside, water is poured on hot rocks to produce steam and high temperatures, and additional rituals could be performed to help people inside the Sweat Lodge undergo purification and cleansing.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Storytelling

Storytelling is a significant channel for connecting individuals to their past, their legends, their history, their identity, and their culture. Every First Nation has its own stories that reflect and reinforce the cultural traditions and its values. And there are stories that are at the very foundation of the society. A vivid example is the story of The Peacemaker, as described and adapted from Onondaga Nation: People of the Hills.

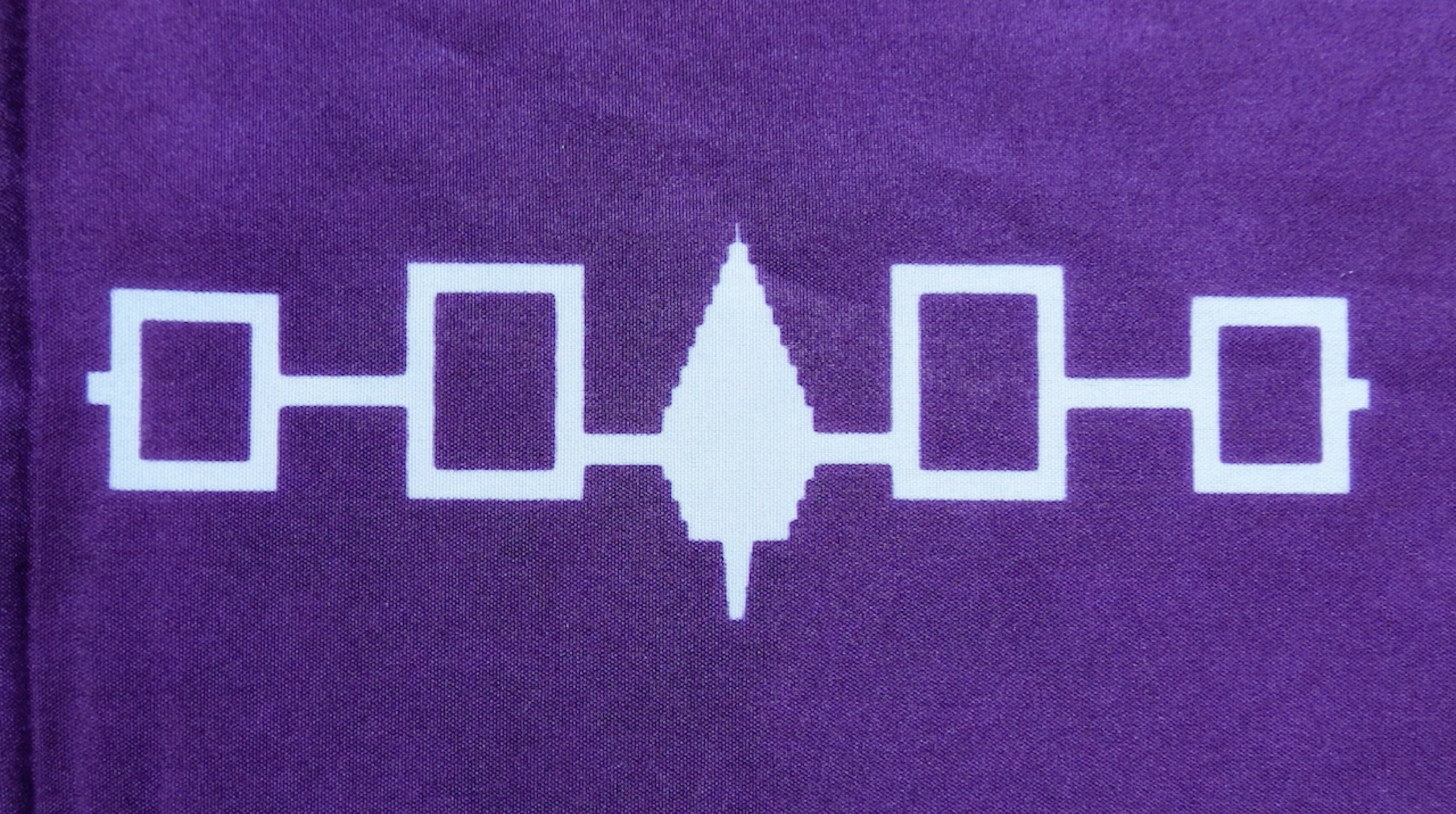

The Hiawatha Belt is made of white and purple beads. The purple represents the universe, and the white represents purity, good thoughts, forgiveness, and understanding. The white open squares represent the Nations united by peace and are connected by a white band that has no beginning or end,

representing forever. The white band does not cross through the centre of each Nation, confirming that the nations are supported and unified by a common bond, and that each Nation is separate in its identity. The tree in the centre is the Tree of Peace.

United under the Great Law of Peace, the Nations formed the Haudenosaunee Confederacy of the Five Nations. Later, with the adoption of the Tuscarora Nation, this union became the Confederacy of the Six Nations. The Chiefs of the Confederacy agreed to always think of the future when making their decisions.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Wampum Belts

First Nations used no written language. However, some First Nations devised creative ways to record significant events and provide a means of remembering the details surrounding the event. One innovative device is the Wampum Belt. A Wampum Belt is a visual record, but not a form of writing. Wampum belts are visual symbols that help trigger and stimulate a “reader’s”

memory of the significance and meaning of the details woven into the belt. Wampum Belts served many purposes: they commemorated events and agreements with other nations, told stories, and described customs, histories or laws. The Hiawatha Belt was described previously. Another Wampum Belt, the Two Row Wampum Belt, is described in Plain Talk 4: Treaties.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

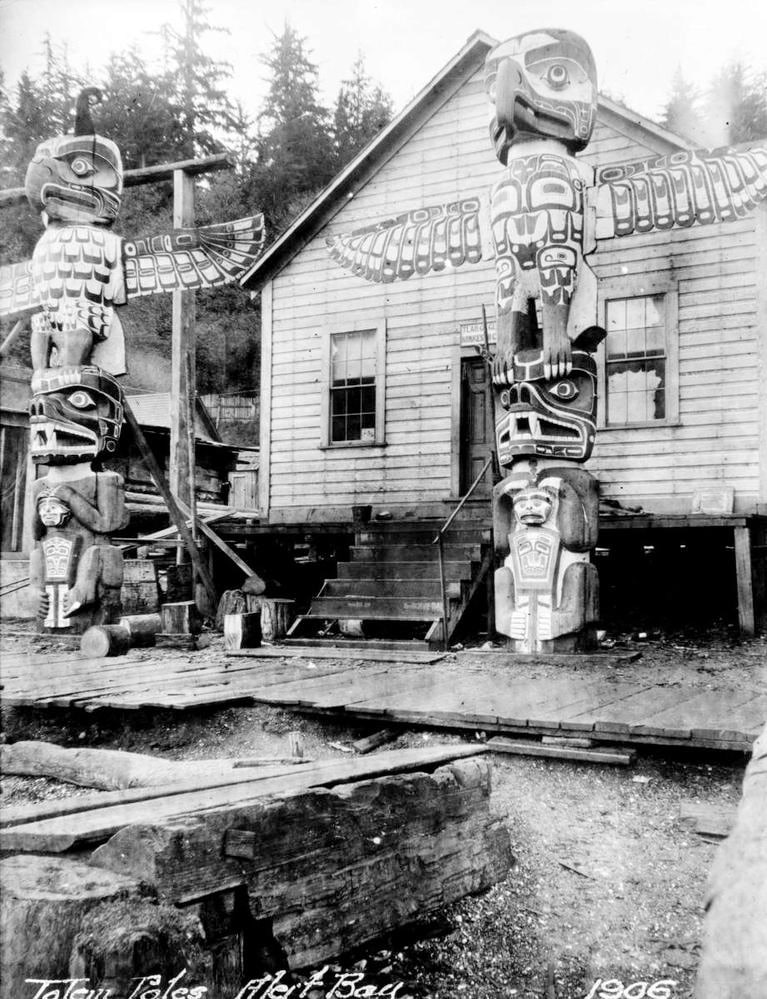

Totem Poles

The First Nations of the Pacific Northwest created totem poles, huge sculptures carved out of large cedar trees. Totem poles served many purposes. They tell stories, myths and legends of the community, recorded significant events of the past or present, and were painted with colours important to the First Nation and their heritage.

The arrangement of symbols in a totem pole tells the story embedded in the pole. Many different animal figures were used to tell a story. The interpretation of each figure or symbol was distinctive to the carver’s First Nation.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Spirituality

Belief in the Creator was central to all First Nations values, traditions and activities. Elders told stories that recounted and reinforced the connection between all members and the natural world. All objects, whether animate or inanimate, were to be treated with honour and respect. Many First Nations peoples share the Seven Grandfather Teachings of the Anishinaabe Peoples—the Values of Truth, Respect, Wisdom, Honesty, Love, Humility, and Bravery. These teachings or laws are known by many other names within various nations.

Each First Nation holds rituals and ceremonies to give thanks to the Creator and the food and material resources in their environments and to honour their values and traditions.

Every First Nation has its own story of its origins, its own Creation legend.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Shelter

The shelter designs of First Nations were intimately related to their environments, resources, and their lifestyles. Some First Nations were migratory, and built portable shelters or shelters that were readily constructed from materials at hand. These shelters consisted on a framework of poles covered with materials like hides of animals or tree bark.

Other First Nations, like the Haudenosaunee, lived in villages dominated by relatively large structures called longhouses, also made of poles and covered in tree bark. Today, the longhouses are the place where ceremonies are conducted.

West coast First Nations built large houses out of the abundant and huge red cedar trees.

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

Social Organization

All First Nations belonged to organized societies in which individuals, families and larger groups (clans and tribes) observed their own social, political and economic values and practices. Some First Nations were patrilineal, in which personal identity derived from the father’s side of the family. Other First Nations were matrilineal, in which personal identity was inherited from the mother’s side.

Geography had an enormous influence on the social organization, diet, and customs of First Nations peoples. For example, because Plains First Nations were blessed with abundant buffalo herds in their environments, they developed a communal hunting culture. The Iroquoian First Nations, on the other hand, were farmers. Because of soil and climate conditions, it was possible for Iroquoian First Nations to grow crops of corn, beans, and squash. The availability of these food staples meant that permanent communities could be established, and formed the basis of their complex, democratic governance systems.

First Nations societies pre-contact with European colonizers were highly developed and sophisticated cultures with systems that nurtured their members, designed technologies suited to their needs and surroundings, and lived harmoniously with their natural environment. This Plain Talk provides only a small picture of the world of First Nations prior to contact.

Chapter 2Pre-Contact

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

References

Aboriginal Rights Resource Tool Kit. Canadian Labour Congress Anti-Racism and Human Rights Department.

Canadian Labour Congress: http://fner.wordpress.com/2012/03/08/aboriginal-rights-resource-tool-kit-pdf

First Nations in Canada:

http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1307460755710/1307460872523

First Nations Teachings & Practices. 2008. Manitoba First Nations Education Resource Centre Inc.

Tenning, A. Walking on the Lands of our Ancestors, 2008, Canada’s National History Society

The Huron Gift to Kahnawà:ke: http://www.wampumchronicles.com/kahnawakehuronwampumbelt.html

Native American Technology & Art: http://www.nativetech.org/wampum/wamppics.htm

Onondaga Nation: People of the Hills: http://www.onondaganation.org/about us/history.html

The Learning Circle: Classroom Activities on First Nations in Canada – Ages 4 to 7:

http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1316530132377/1316530184659

http://www.dickshovel.com/500.html

Understanding and Appreciation of First Nations History and Culture. First Nations Education Initiative Inc: http://www.fneii.ca

Image Sources

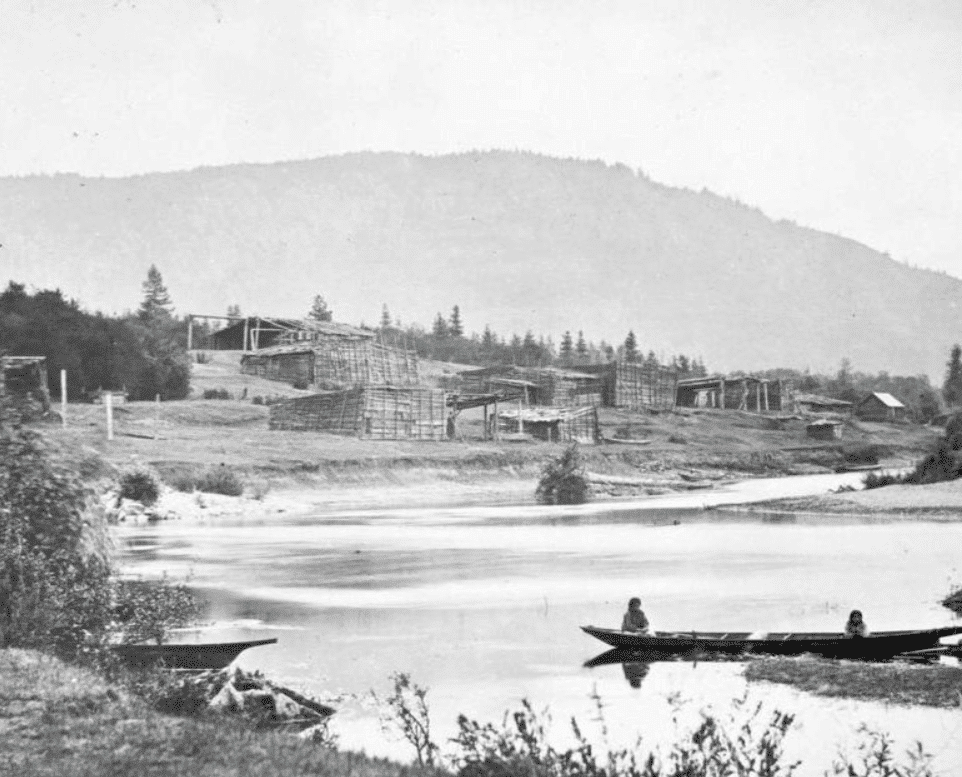

pg.2 The Quamichan [Hul’qumi’num] Village. Vancouver Island, East Coast. [Possibly the village of Kw’amutsun on the Cowichan River.]

Frederick Dally Fonds [ca. 1866-1870]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

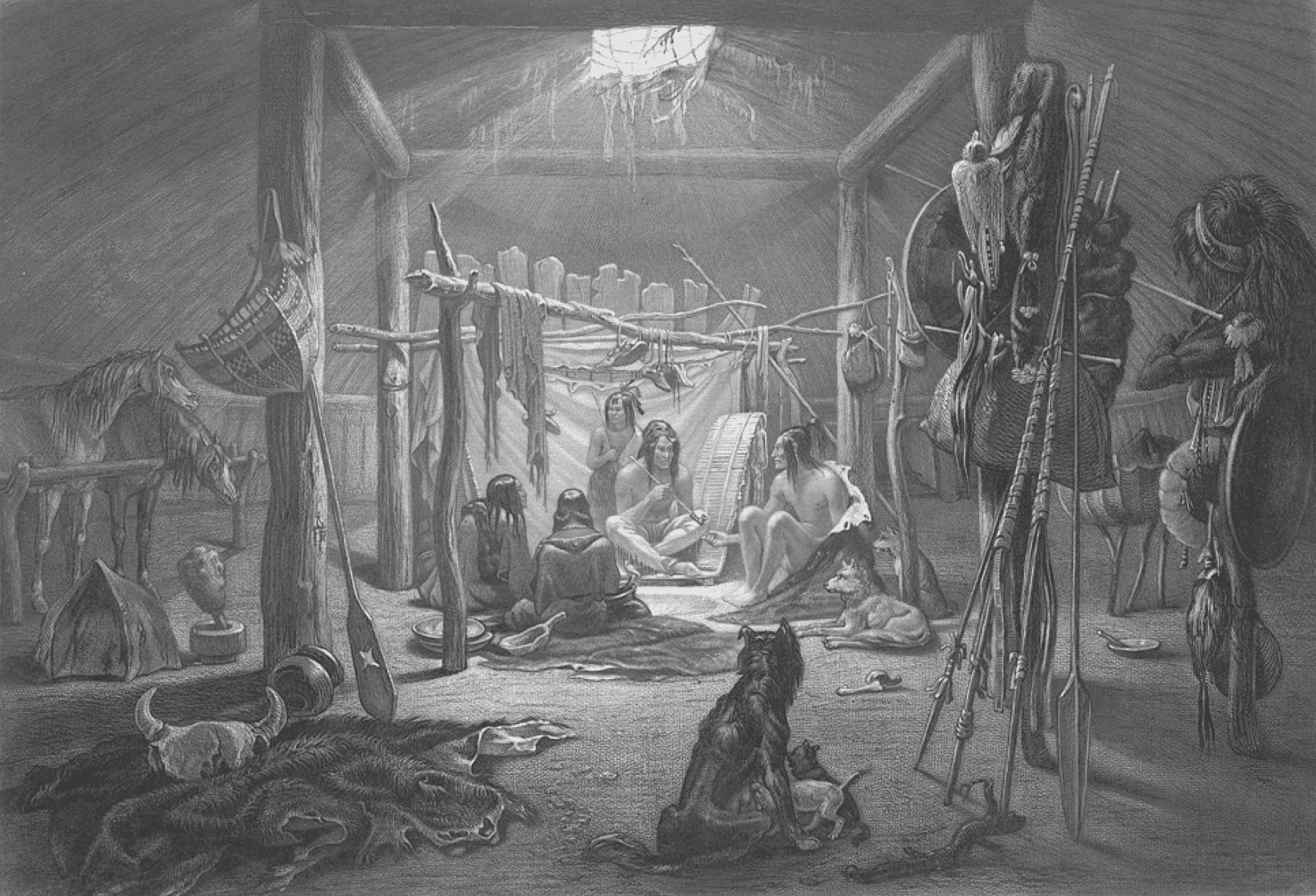

pg.3 Interior of the Hut of a Mandan Chief.

Engraving of a watercolour by Karl Bodmer

[ca. 1832] WHI-6341

Wisconsin Historical Society/Archives of Ontario

pg.4 From “The North American Indian” by Edward S. Curtis; Volume 9; Plate No. 302; Skokomish fishing camp; two natives on beach, canoe in foreground. Photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis [ca. 1912]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

Plain Talk 2 | Pre-Contact

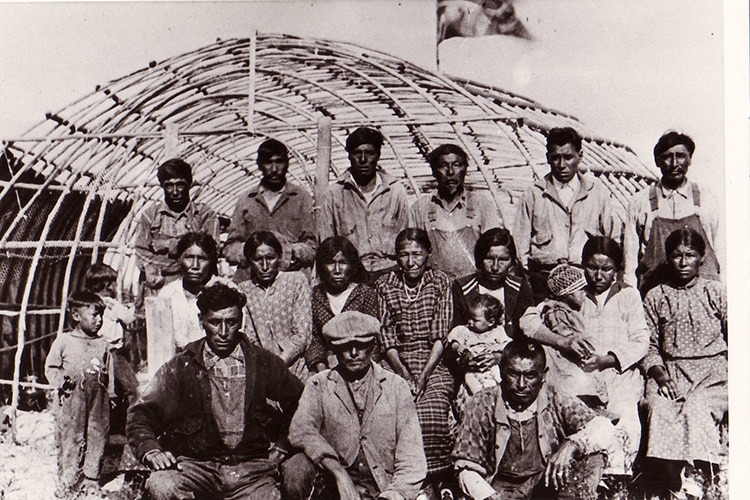

A First Nations family in the Yukon Territory. Photographer unknown [ca.?]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

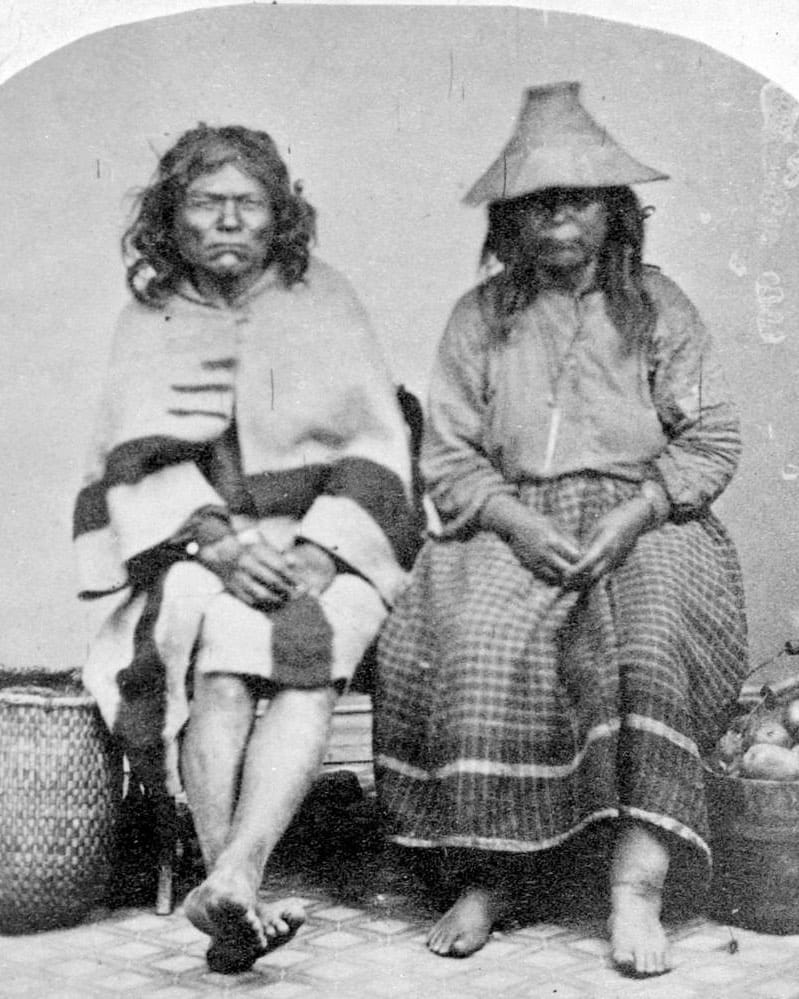

Cowichan First Nation man and woman potato sellers.

Frederick Dally Fonds [ca. 1866-1870]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

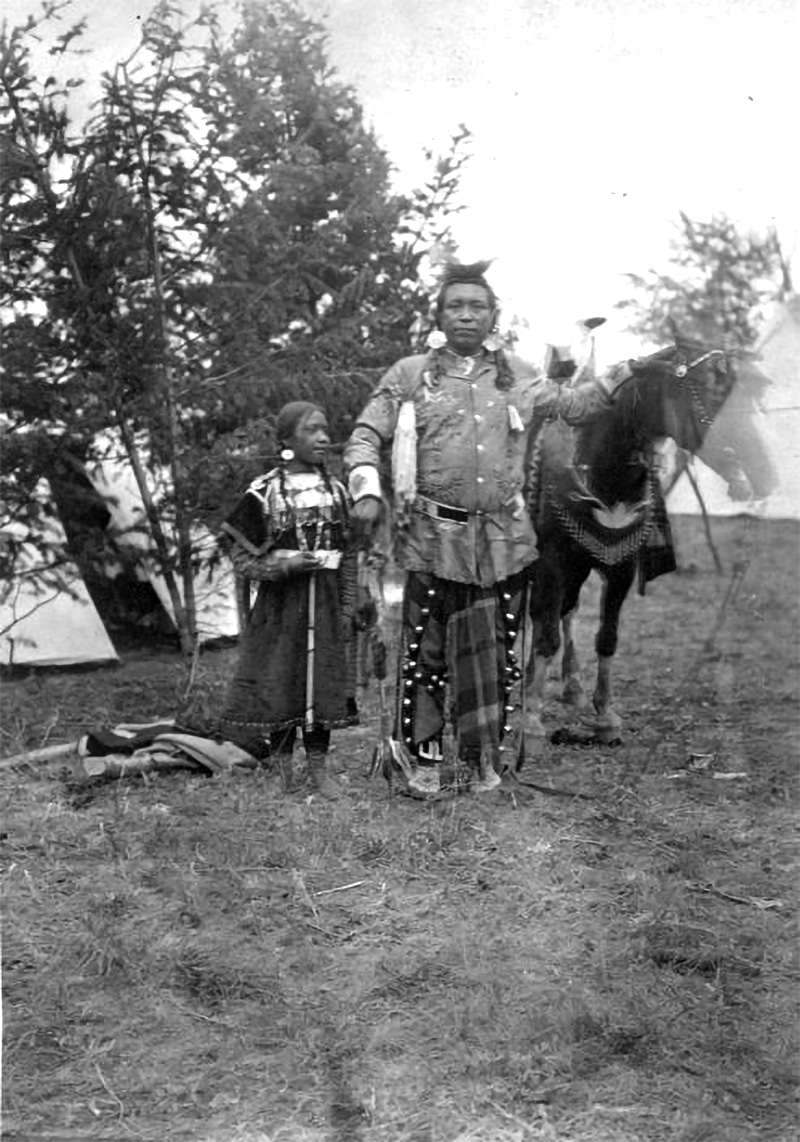

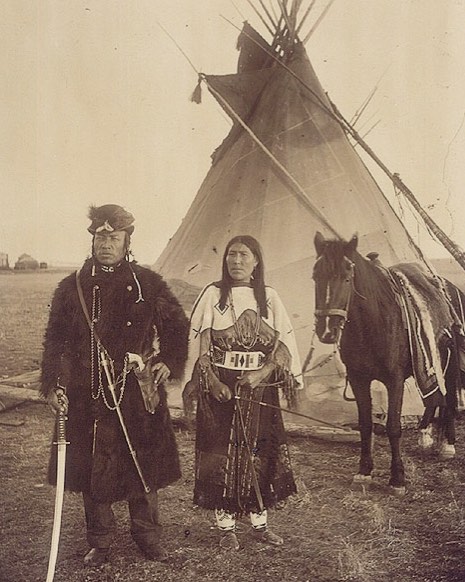

Dog Child, a North West Mounted Police scout, and his wife, The Only Handsome Woman, members of the Blackfoot Nation, Gleichen, Alberta [ca. 1890]. Ed Tompkins, Jeffrey Thomas portraits [ca. 1890]. Canadian National Archives

Copy of a portrait of Pauline Johnson, Six Nations poetess.

Photographer unknown [ca. 1885]

Archives of Ontario

Maun-gua-daus (or Maun-gwa-daus) alias George Henry (born ca. 1807), original chief of the Ojibwa Nation of Credit (Upper Canada) and interpreter employed by Indian Affairs.

Ed Tompkins, Jeffrey Thomas portraits [ca. 1846].

Canadian National Archives

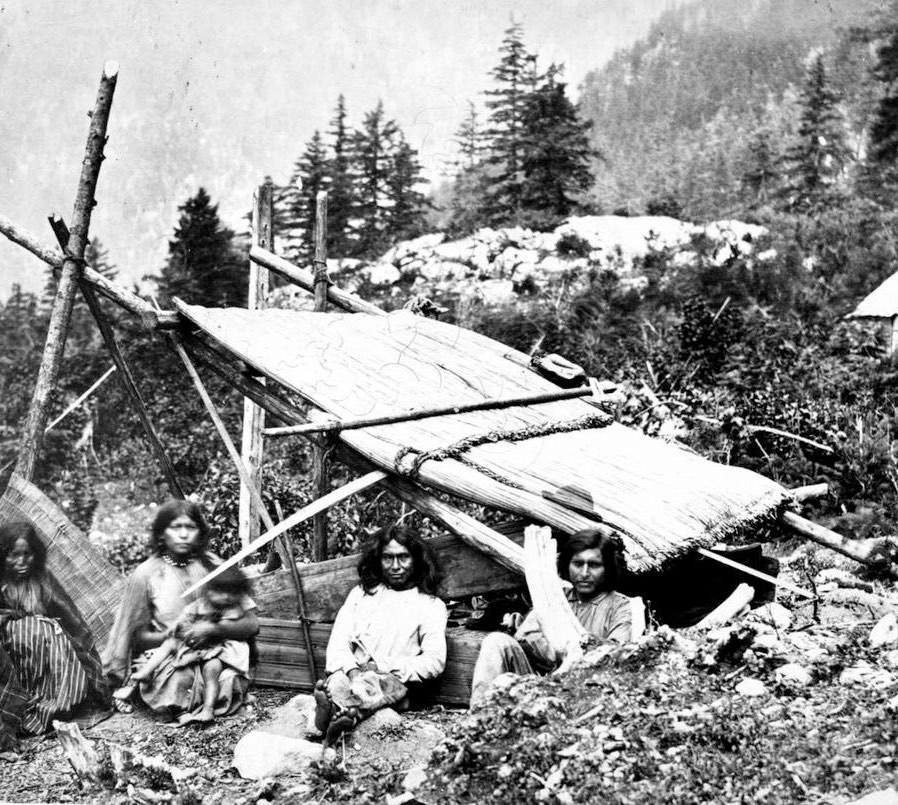

pg.5 Encampment of Scachett [sic] [Skagit?] Indians at New Westminster, Fraser River, British Columbia

Frederick Dally Fonds [ca. 1866-1870]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

pg.6 Tyendinaga Pow Wow, Tyendinaga Ontario Photographer Terri-Lynn Brennan

[ca.2017]

pg.7 First Nations women and girls at Ma-ate in Quatsino Sound

Photograph by Oregon Hastings, [ca. 1879]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

Cleaning salmon at Stuart Lake.

Photographer Frank Cyril Swannell [ca. 1909]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

White Eye Jack, Lena and Klootch.

Photographer Frank Cyril Swannell [ca. 1928]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

Alaskan First Nations children

Photographer unknown [ca. ?]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

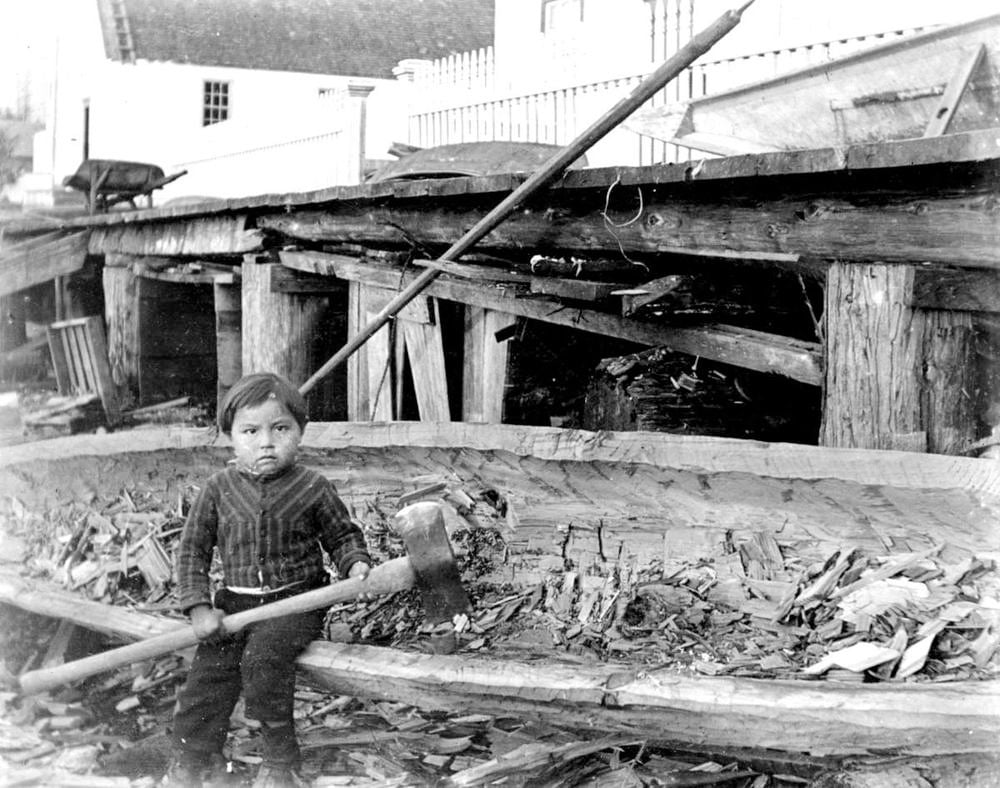

First Nations child and partially completed canoe; Indian Mission, Vancouver.

Photographer unknown [ca. ?]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

First Nations Man and Child in traditional clothing. Photographer Frank E. Schoonover [ca.1905?]

Alberta Provincial Archives