Plain Talk 5The Indian Act

Chapter 1The Indian Act

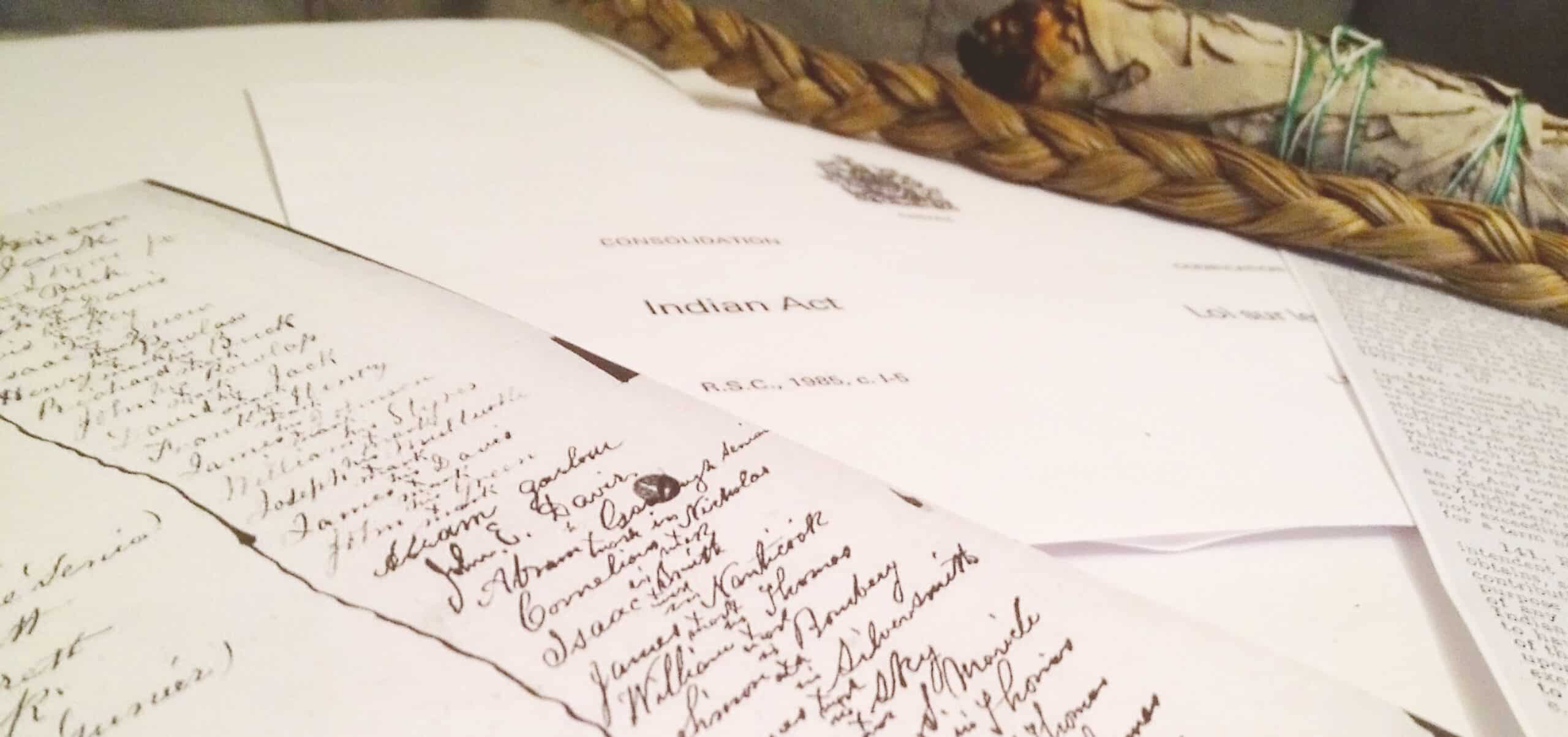

The Indian Act of 1876 is a legal document and a set of laws that gave the Government complete control over the lives of First Nations peoples. This chapter will provide information on the Indian Act and how its policies have affected First Nation people throughout Canada’s history and still affect them today. While some regulations have changed; the Indian Act has shaped and continues to impact the relationship between First Nations and the Canadian Government.

Section 1

Introduction to the Indian Act

The Indian Act has been described, justifiably, as archaic, outdated, colonial, racist, paternalist, and repressive. Shockingly, it is still in effect today.

“[The Indian Act] has… deprived us of our independence, our dignity, our self-respect and our responsibility.”

—Kaherine June Delisle, Kanien’kehaka First Nation Kahnawake, Quebec

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

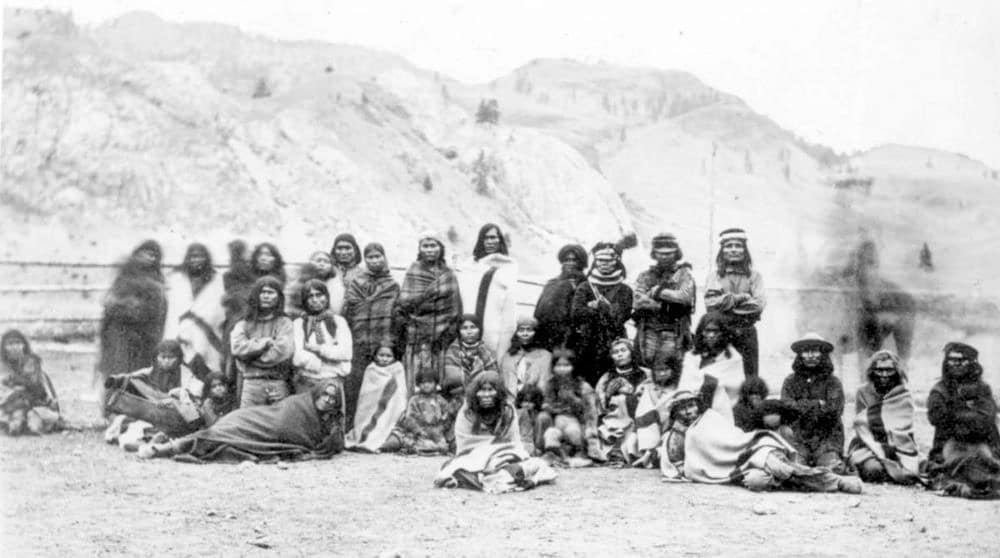

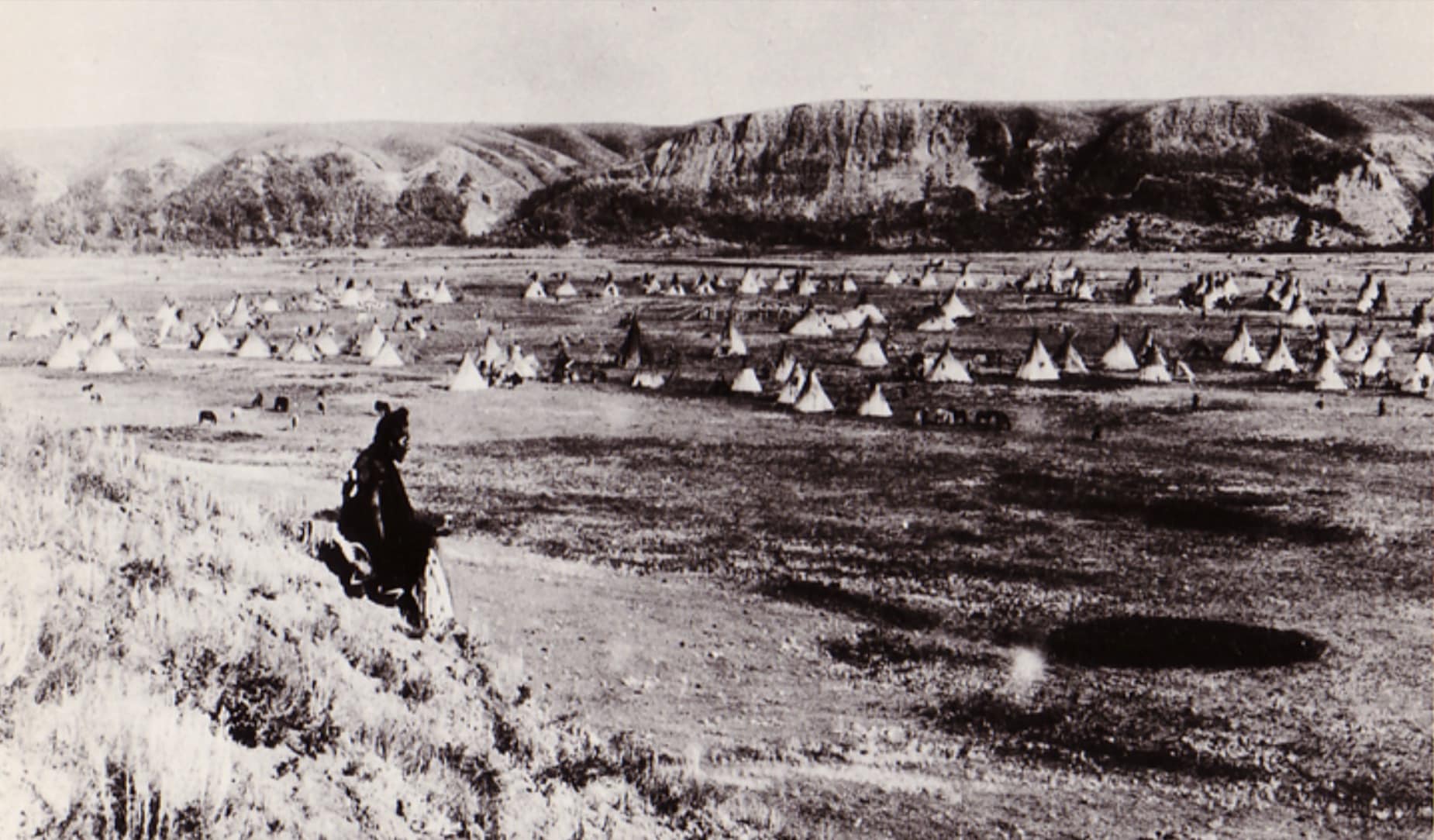

Historically, control over First Nations was a British responsibility that passed to Canada after Confederation. As the fur trade ended, First Nations peoples were increasingly seen as a barrier to government plans for the settlement of western Canada. The Government called it “the Indian problem”.

The Government responded to this “problem” by creating the Indian Act in 1876. The Indian Act is a legal document and a set of laws that gave the Government complete control over the lives of Indian peoples.

There were two objectives:

The Indian Act regulates and administers the lives of registered Indians and reserve communities. It imposes imperial political control and enforces restrictions on First Nations movement, their right to live where they please, and their right to practice their culture and traditions.

“The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change.”

—Sir John A. McDonald, 1887

The Gradual Civilization Act passed in 1857 and sought to assimilate each Indian into Canadian settler society through enfranchisement. Historically, if a First Nations individual wanted to vote or attend post-secondary school, they would have to renounce their Status. The purpose of assimilation was to absorb First Nations people into Canadian society.

The Indian Act built upon this notion of assimilation, forcing First Nations to give up their culture and languages. This Act also introduced the elective band council system, that emulates colonial democracy. This system still exists in First Nations governance today.

A famous statement in 1920 by Duncan Campbell Scott, poet, essayist, and Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, stated the prevailing attitude of his day:

Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian department.

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

The Indian Act Timeline

Tap the dates to learn more:

-

The Gradual Civilization Act

An act to encourage the gradual civilization of Indian Tribes through compulsory enfranchisement. The Act denotes that any First Nations male who was free of debt, literate and of good moral character could be awarded full ownership of 59 acres of reserve land. However, he would then be considered enfranchised, cease to be an Indian and cut all ties to his band.

-

-

The Gradual Enfranchisement Act

An act for the gradual enfranchisement of Indians and the management of Indian affairs, and to include changes to the enfranchisement process. The Act increased government control of on-reserve political systems through the Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs who determined when and how First Nations elections of governance would take place. The Canadian Government replaced tradition forms of choosing First Nations leadership with the voting system for Chief and Council to take place every two years.

-

-

The Indian Act

An “Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians,” the original Indian Act, was passed. The Indian Act was not part of any treaty made between First Nations peoples and the British Crown. The sole purpose of the act was to assimilate and colonize First Nations peoples.

-

-

Amendments to Indian Act

“An Act to amend ‘The Indian Act, 1876′” amended the act to: allow “half-breeds” to withdraw from Treaty; to allow punishment for trespassing on reserves; to expand the powers of Chief and Council to include punishment by fine, penalty or imprisonment; and to prohibit houses of prostitution.

-

-

Department of Indian Affairs

Indian Act amended to make officers of the Department of Indian Affairs, including Indian Agents, legal justices of the peace, able to enforce regulations under act. The following year they were granted the same legal power as magistrates. Further amended to prohibit the sale of agricultural produce by Indians in Prairie Provinces without an appropriate permit from an Indian agent. This prohibition is still included in the Indian Act, though it is not enforced.

-

-

Prohibiting Spiritual Ceremonies

Amended to prevent elected band leaders who have been deposed from office from being re-elected. Further amended to prohibit First Nations peoples from conducting or participating in spiritual ceremonies such as the potlatch and Tamanawas dances.

-

-

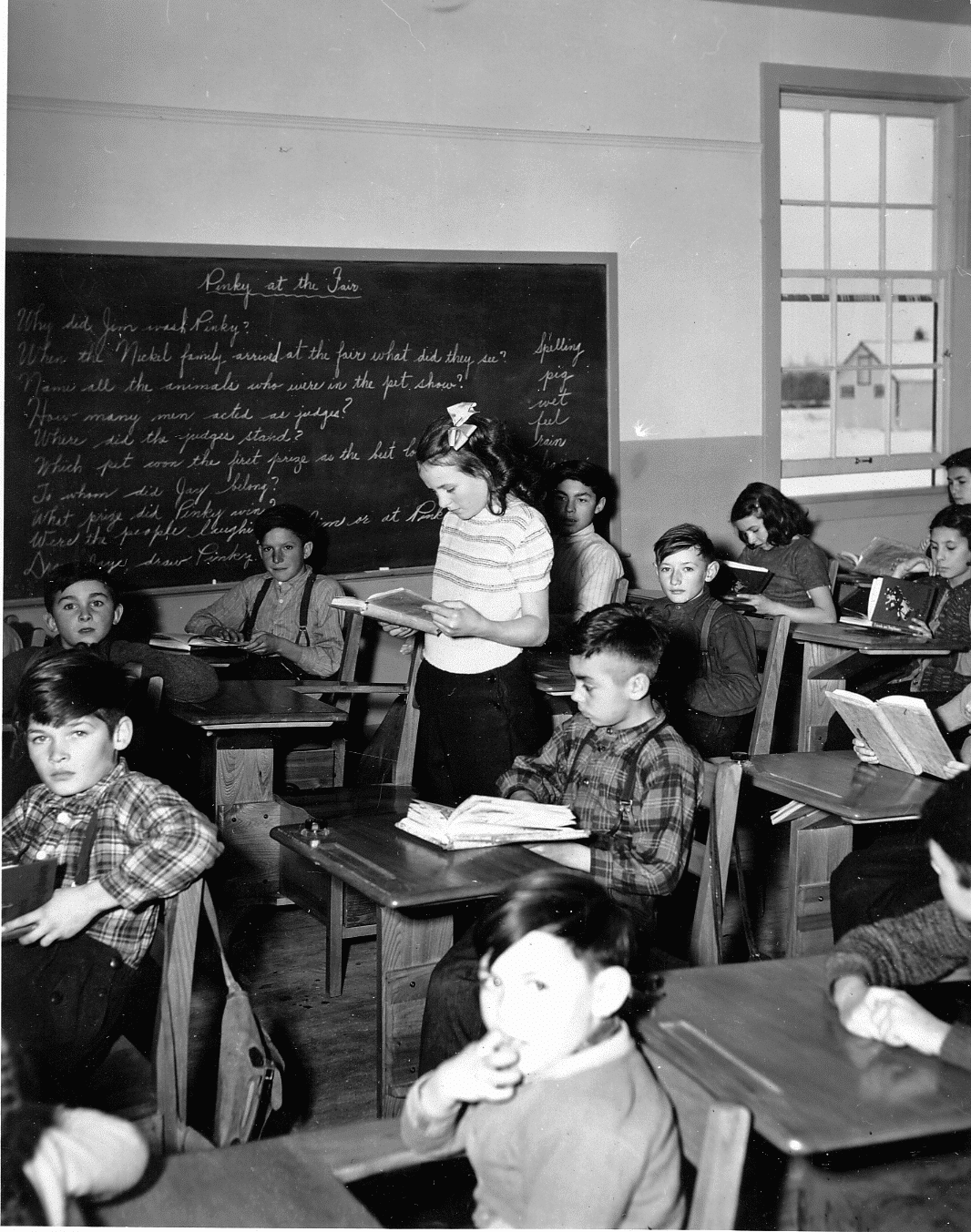

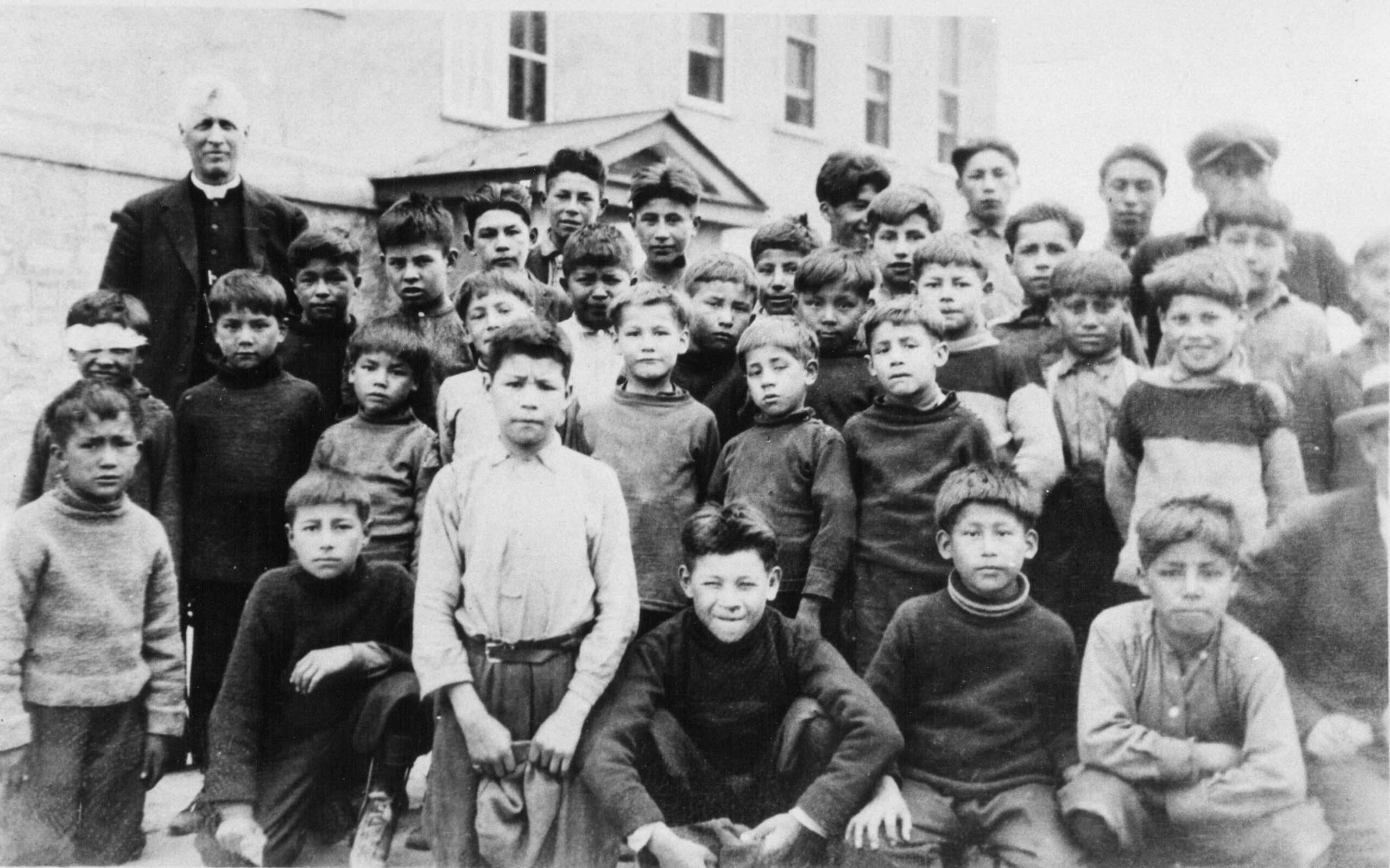

Compulsory Schooling

Act amended to force attendance of Indian youth in school. Industrial schools ran from 1883-1923. After 1923 these schools became known as “residential schools.” Part of the federal government assimilation policy focused on eliminating First Nations children’s cultural beliefs and practices. First Nations parents were fined or jailed if they did not send their children to residential schools.

-

-

Forced Removal

Amended to allow First Nations people to be removed from reserves near towns with more than 8,000 residents.

-

-

Oliver Act

Amended to allow municipalities and companies to expropriate portions of reserves. Further amended to allow a judge to move an entire reserve away from a municipality. These amendments were also known as the Oliver Act.

-

-

Amendments for Western Indians

Amended to require western Indians to seek official permission before appearing in “Aboriginal costume” during any “dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant.”

-

-

Leasing Reserve Land to Non-Aboriginals

Amended to allow the Superintendent-General to lease out uncultivated reserve lands to non-Aboriginals if it was to be used for farming or pasture.

-

-

Residential Schools

Amended to make it mandatory for Aboriginal parents to send their children to Indian residential school. Further amended to allow for the involuntary enfranchisement (and loss of treaty rights) of any status Indian considered fit by the Department of Indian Affairs, without the possession of land previously required for those living off reserve. This amendment was repealed two years later but reintroduced in a modified form in 1933.

-

-

Impact of Land Claims

Amended to prevent anyone (Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal) from soliciting funds for Indian legal claims unless they secured a special license from the Superintendent-General. This prevented any First Nation from pursuing Aboriginal land claims.

-

-

Impositions on Band Council Meetings

Amended to allow Indian agents to direct band council meetings, and to cast a deciding vote in the event of a tie.

-

-

Removal of Provisions

The 1951 amendments removed some of the provisions in the legislation, including the banning of spiritual dances and ceremonies, the sale and slaughter of livestock, and the prohibition on pursuing claims against the government. First Nations peoples were now permitted to hire lawyers to represent them in legal matters, and status women were now able to vote in band elections.

- Further amendments allowed for the compulsory enfranchisement of First Nations women who married non-status men (including Métis, Inuit and non-status Indian, as well as non-Aboriginal men), thus causing them to lose their status, and denying Indian status to any children from the marriage.

-

-

Bill C-31

Bill C-31 was introduced to void the enfranchisement process, which allowed status Indian women the right to keep or regain their status even after “marrying out” and to grant status to the children (but not grandchildren) of such a marriage. Under this amendment, full status Indians are referred to as 6–1. A child of a marriage between a status (6–1) person and a non-status person qualifies for 6–2 (half) status. If that child grows up and in turn married a non-status person, the child of that union would be non-status. If a 6–2 marries a 6–1 or another 6–2, the children revert to 6–1 status. Blood quantum is disregarded, or rather, replaced with a “two generation cut-off clause”. It was estimated that approximately half of status Indians were married to non-status people, meaning Bill C-31 legislation would complete legal assimilation in a matter of a few generations.

-

-

Voting Off-Reserve

Amended to allow band members living off reserves to vote in band elections and referendums.

-

-

Bill C-3

Bill C-3 was introduced that amended provisions that were found unconstitutional. These amendments ensured that eligible grandchildren of women who lost status as a result of marrying non-status men became entitled to registration (Indian status). As a result of this legislation approximately 45,000 persons became newly entitled to registration.

-

-

Métis and Non-Status Indians

Amendments to include 200,000 Métis and 400,000 non-status Indians in the federal responsibility for Indians after a 13-year legal dispute.

-

-

Daniels v. Canada

In 2016 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on Daniels v. Canada or the ‘Daniels Decision’. The Daniels decision stated that Metis and non-status Indians are considered under the term ‘Indian’ under section 91 (24) of the Constitution Act, 186. The Daniels decision does not provide Metis or non-Status First Nations status under the Indian Act.

-

-

Bill S-3

Bill S-3, Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).

-

Section 1

Regulations under the Act

The Indian Act was designed to address the Indian problem by singling out a segment of society, largely on the basis of race, removing much of their land and property from the commercial mainstream, and giving the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada and other government officials a degree of discretion that is not only intrusive but frequently offensive.

“We all want to move beyond the Indian Act’s control and reconstitute ourselves as Indigenous peoples and Nations with fundamental inherent rights”

—Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Indian Status

According to the Act, First Nations people (Indians) were deemed not to be people. Right up until 1951, the definition of a person was defined in the statute as an individual other than an Indian. The Indian Act did provide that Indians could become persons by voluntarily enfranchising (giving up their status) and, in many circumstances, they were involuntarily enfranchised by the Act.

Some ways that enfranchisement could happen were by serving with the Canadian Armed forces, attaining post-secondary education, or for a First Nations woman to marry a non-First Nations man.

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Restriction of Freedoms

The Indian Act placed in the hands of the federal government complete control over First Nations politics, finance, culture, and personal lives. Ceremonies like the potlatch and the Sun Dance that had been practiced for thousands of years were outlawed and forbidden. In 1914, the Act barred the wearing of Aboriginal costume in any dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant, unless the Minister approved. The possession of totem poles, grave houses, or even a rock embellished with paintings or carvings was forbidden, unless the Minister approved.

People were not permitted to move about freely, if they did so they could be jailed or fined if, for example, they were deemed to linger in pool halls.

The authority of the Crown even extended to an individual’s Last Will and Testament. A Will could be declared to be void if, in the opinion of the authorities, it was deemed to be unsuitable, inequitable, inferior, unsound, invalid, anything at all.

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Swipe through the gallery to view restrictions established by the Indian Act

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Residential Schools

The Indian Act created Residential Schools and forced a new form of education on First Nations peoples. The decades long strategy of 130 government-funded Residential Schools was to kill the Indian in the child. Under the Act, more than 150,000 children were legally shipped off to institutions where they would have their hair cut, their language killed, their relationships with family and community severed, their sense of belonging destroyed, and their physical, emotional, mental and spiritual health compromised. The Indian Act did provide in minute detail for punishment and consequences. For example

when deemed to be Truant, the child could be apprehended and conveyed to school, using as much force as the circumstances require. The Act did not provide for love, support, respect, and caring.

The last of the Residential Schools did not close until 1996. Today, there are an estimated 80,000 former students still living and the catastrophic impacts of the Residential Schools have been, and will continue to be, felt for generations. See Plain Talk 6, Residential Schools.

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Land

The Indian Act did not allow First Nations people to own land. Over time, measures originally intended to protect the land base were changed to open up reserve lands for farming, settlement, and other purposes by non-First Nations people. The Act set down whether and how land should be cultivated or not cultivated, and whether and how people could buy and sell livestock. It decreed whether and where and how roads should be built and maintained, and where the roads should go, and how fast or slow people could travel on these roads, and even where they could park.

Treaty provisions that permitted the federal government to take up reserve lands for public works of Canada were modified in the Act to allow companies with the power to extract resources to exercise them on reserve. When First Nations people complained of administrative abuses and began to push their claims of Aboriginal title in non-Treaty areas or in areas that were seen as traditional lands, the Act was amended to make it an offence to retain a lawyer for the purpose of advancing a claim. Not surprisingly, the land base was reduced, often in return for nominal consideration or no consideration.

A 1927 amendment required anyone who solicits funds for Indian legal claims to obtain a license from the Superintendent General of Indian affairs. This severely limited the ability of First Nations to pursue land claims through the courts. A major overhaul of the Indian Act in 1951 did see many of these restrictions struck down.

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Voting Rights

The Indian Act did not allow First Nations people to vote in a federal election until 1960. Even though for centuries, First Nations people had capably established their own systems of government and managed their own societies and communities, under the Indian Act, First Nations people were not permitted to vote in federal elections. This ban continued until 1960. They could not sit on juries, and they were exempt from conscription in time of war. However, it should be noted that the percentage of volunteers was higher among First Nations people than any other group. One way for First Nations to vote was to surrender up their First Nation Status, or in other words, enfranchise. First Nations were encouraged to enfranchised and even offered incentives such as land.

Amendments

Some amendments have been made to the Indian Act, including lifting of the ban on ceremonies and fundraising, permission to vote, and Bill C-31 to re-establish some First Nations status. Bill C-31 also reinstated those persons and their children who had previously lost status. In the current Indian Act, there is no voluntary or involuntary enfranchisement and marriage is a neutral act: no one gains or loses status based on their gender.

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

Moving Beyond the Indian Act

The situation has been summarized very well by the lawyer, William Henderson in an article at http://www.bloorstreet.com/200block/sindact.htm.

The Indian Act seems out of step with the bulk of Canadian law. It singles out a segment of society, largely on the basis of race, it removes much of their land and property from the commercial mainstream, and gives the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and other government officials a degree of discretion that is not only intrusive but frequently offensive.

The Act has been highly criticized on all sides. Many want it abolished because it violates expected standards of equality. Others want First Nations to be able to make their own decisions as self-governing peoples and they see the Act as inhibiting that freedom. Even within its provisions, people see unfair treatment; for example, First Nations who live on reserve and those who reside elsewhere. In short, this is a statute of which few speak well.

An argument could be made that the Indian Act should simply be abolished. However, for complex reasons, the sudden disappearance of the Act could create even more problems.

At the 2010 annual meeting of the Assembly of First Nations, National Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo called on Ottawa to repeal the Indian Act within five years. He proposed replacing the law with a new arrangement that would allow all parties to move forward on land claims and resource sharing.

Certain nations and organizations, such as the Maa-nulth First Nation, have moved towards Self-Governance agreements. Though these do not exempt First Nations from the Indian Act, it allows more autonomy for the nations to make decisions about their education, economy, resources etc.

Chapter 2The Indian Act

Plain Talk 5 | The Indian Act

References

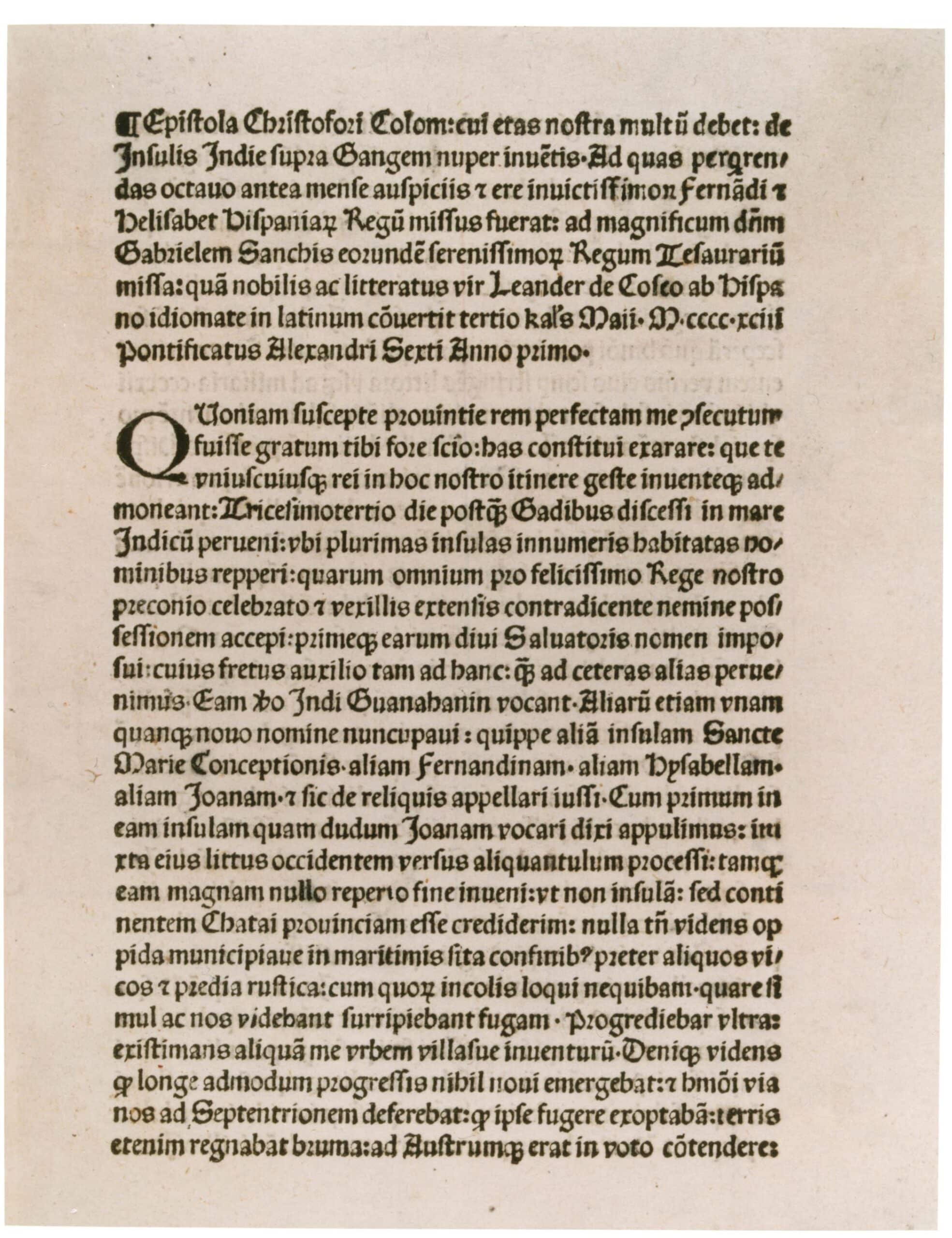

Columbus Reports on his First Voyage, 1493, History Now, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved July 8 , 2019, from https://www.gilderlehrman.org/content/columbus-reports-his-first-voyage-1493.

“Enfranchisement.” Indigenousfoundations, https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/enfranchisement/.

Joseph, Bob. “21 Things You May Not Have Known About The Indian Act.” 21 Things You May Not Have Known About The Indian Act, https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/21-things-you-may-not-have-known-about-the-indian-act-.

Legislative Services Branch. “Consolidated Federal Laws of Canada, Indian Act.” Indian Act, 26 July 2019, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-5/.

Northern Affairs Canada. “Background on Indian Registration.” Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 28 Nov. 2018, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1540405608208/1540405629669#_Bill_C-31_and.

- Northern Affairs Canada. “Indian Status.” Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications Branch, 9 July 2019, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032374/1100100032378.

Northern Affairs Canada. “What Is Indian Status?” Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada; Communications Branch, 9 Aug. 2018, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032463/1100100032464.

What Have we Learned?: Principles of Truth and Reconciliation (Rep.). (2015). Retrieved July 8, 2019, from http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Principles_English_Web.pdf.