Plain Talk 4Treaties

Chapter 1Treaties

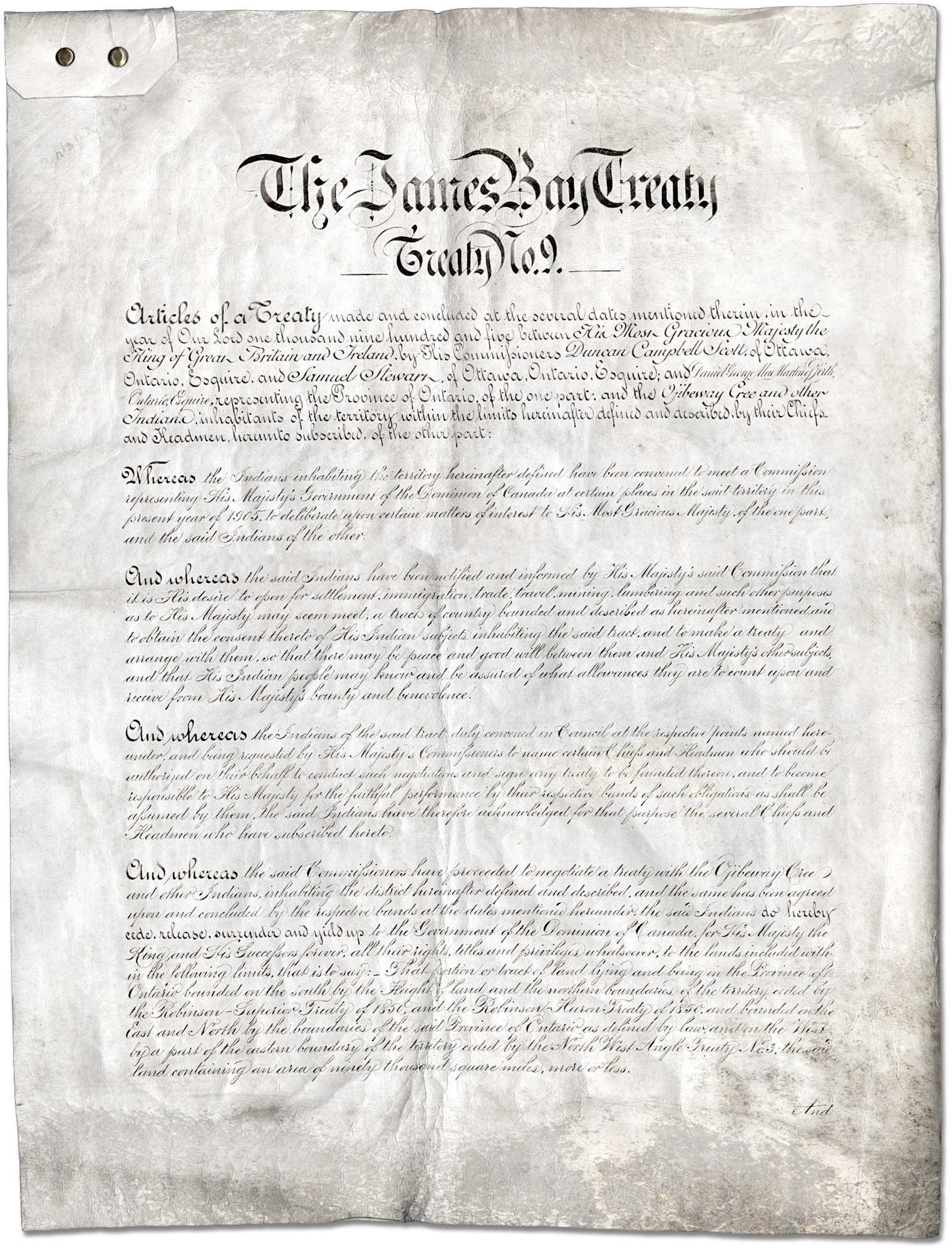

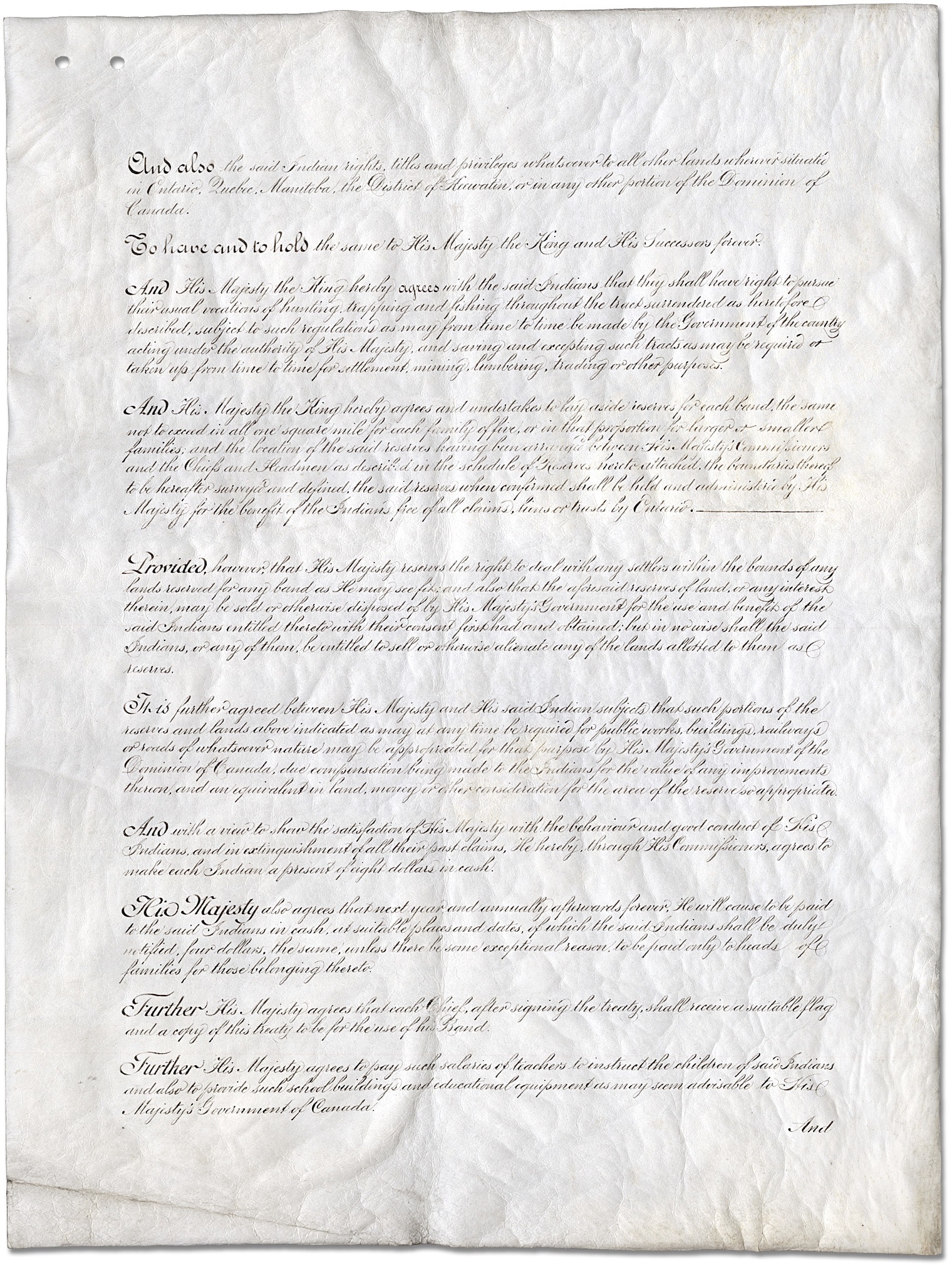

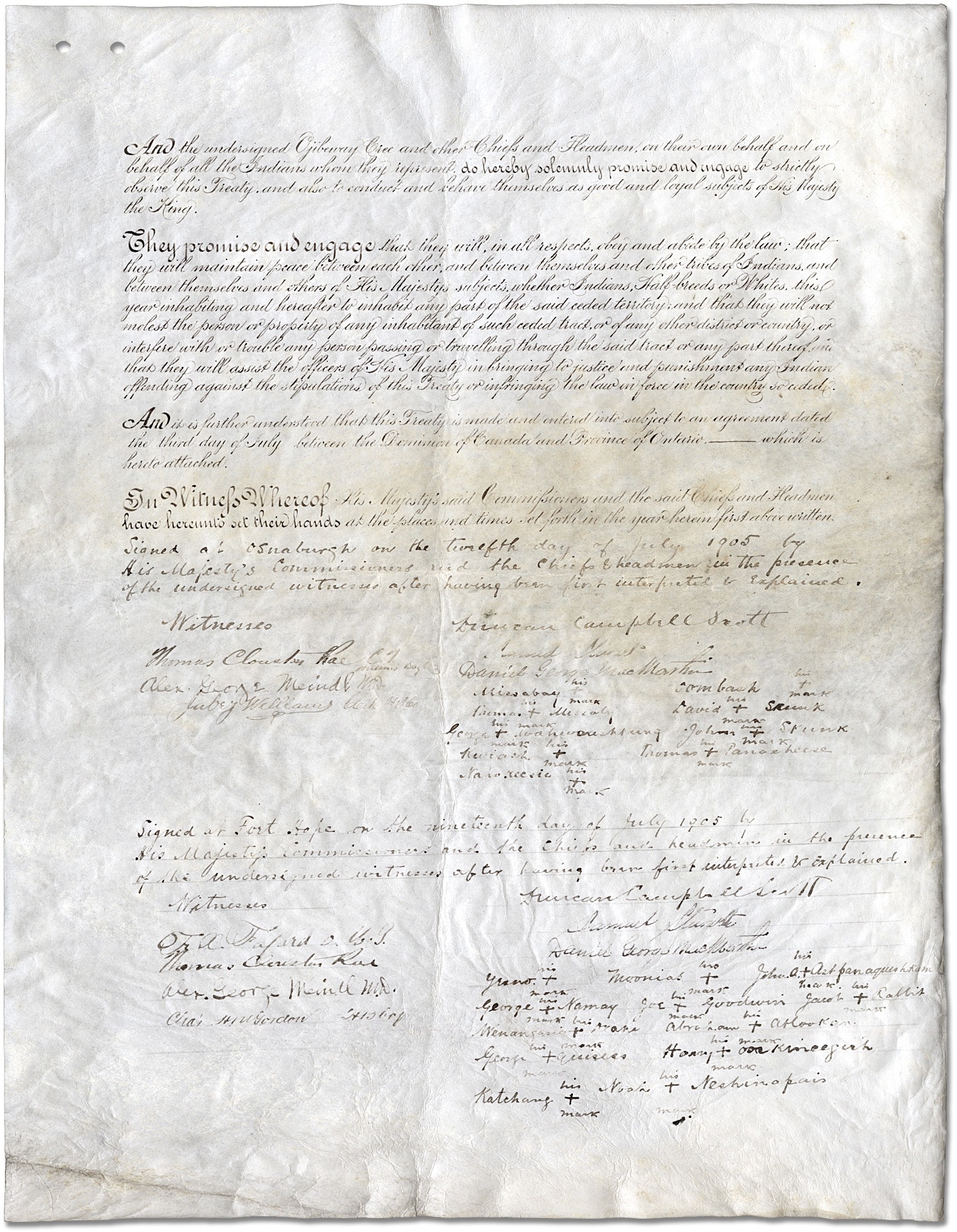

Treaties 1-11, most commonly known as the Numbered Treaties, were sign between 1871-1921 between First Nations and the British Crown.

Section

Treaties and Why They are Important

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, defines a treaty as “an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation.”

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

The Supreme Court of Canada, in R. v. Sioui, 1990, noted “What characterizes a treaty is intention to create obligations, the presence of mutually-binding obligations and a certain measure of seriousness. Section 35 of the Constitution of Canada recognizes and affirms Rights arising from treaties, however, as you will read later, there is often disagreement between the Crown and First Nations over the interpretation of treaties.

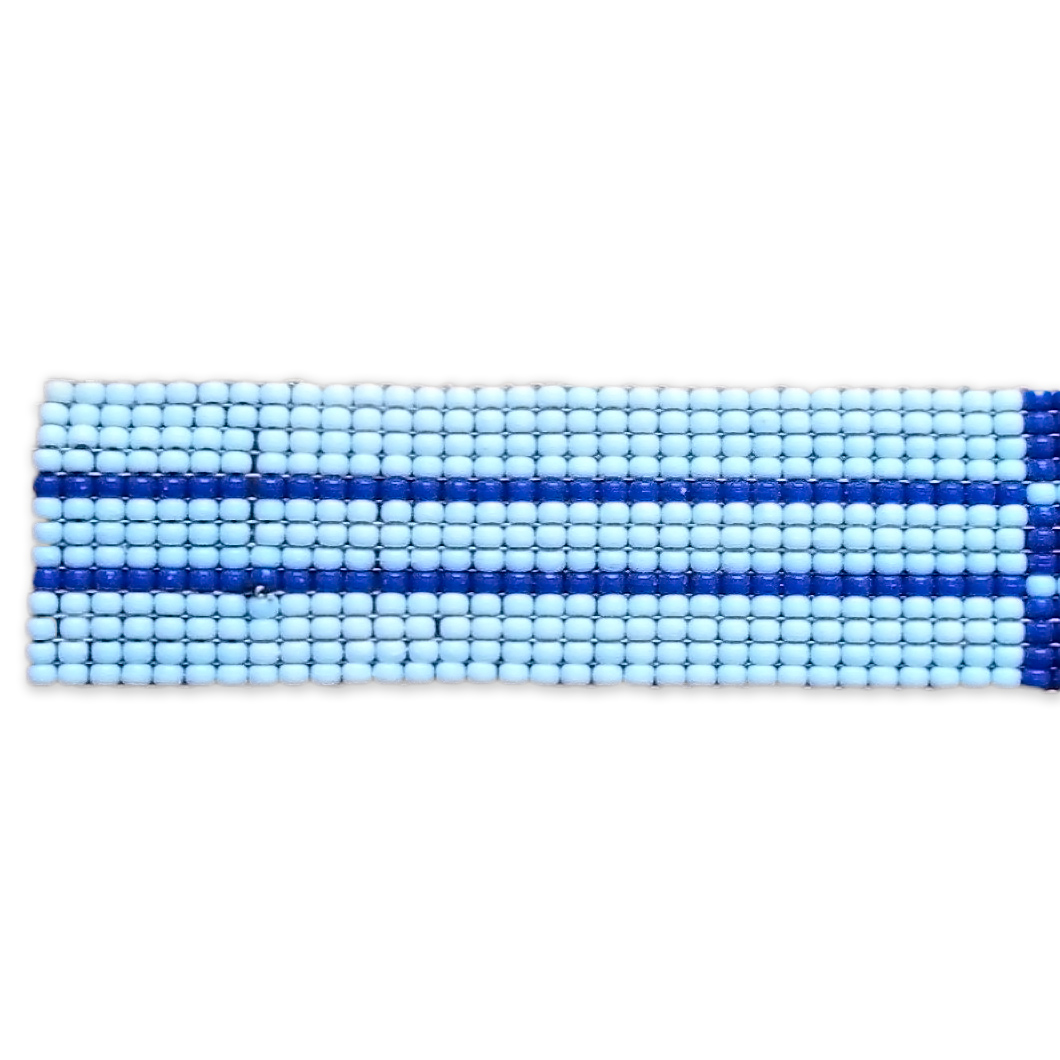

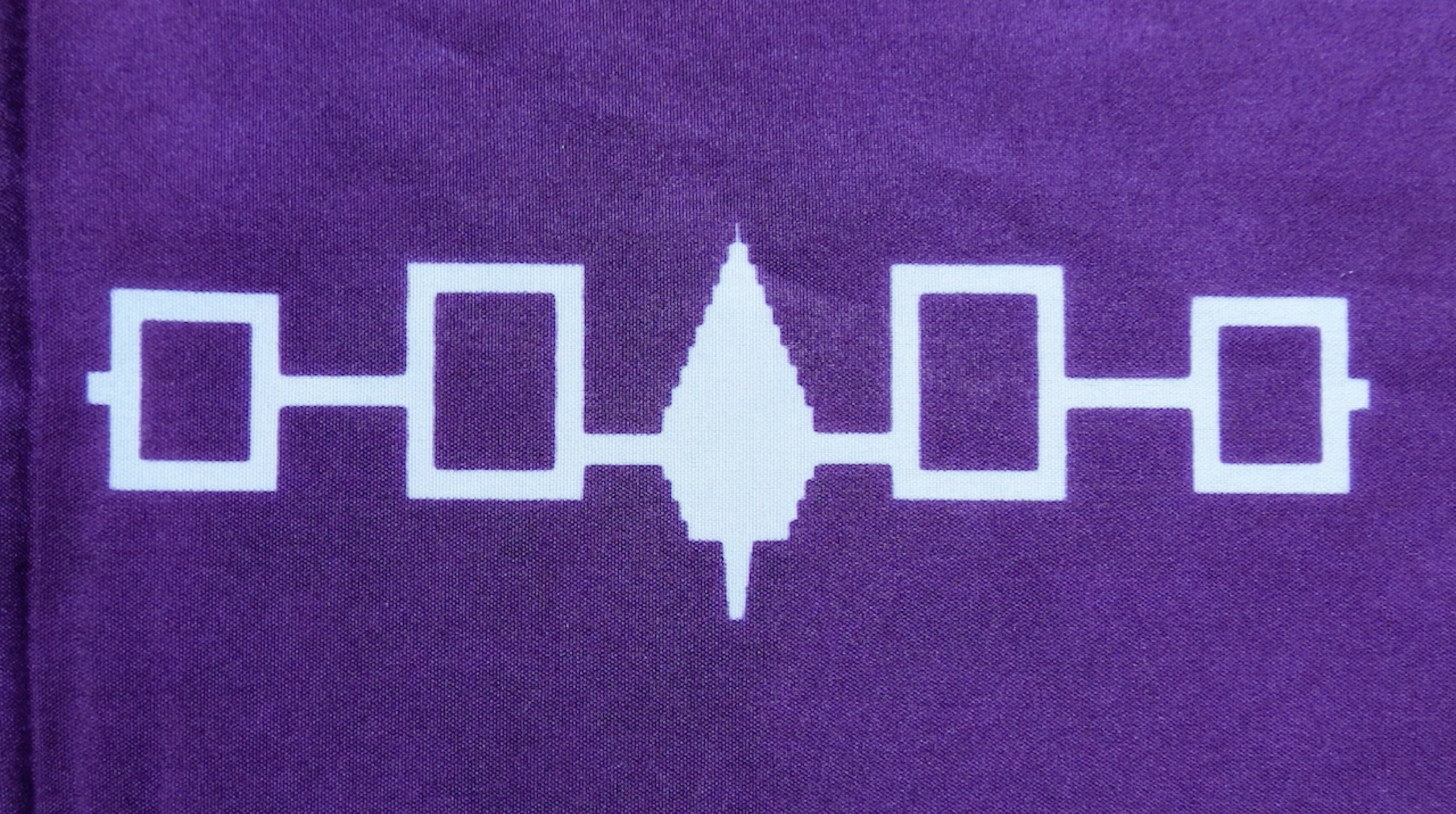

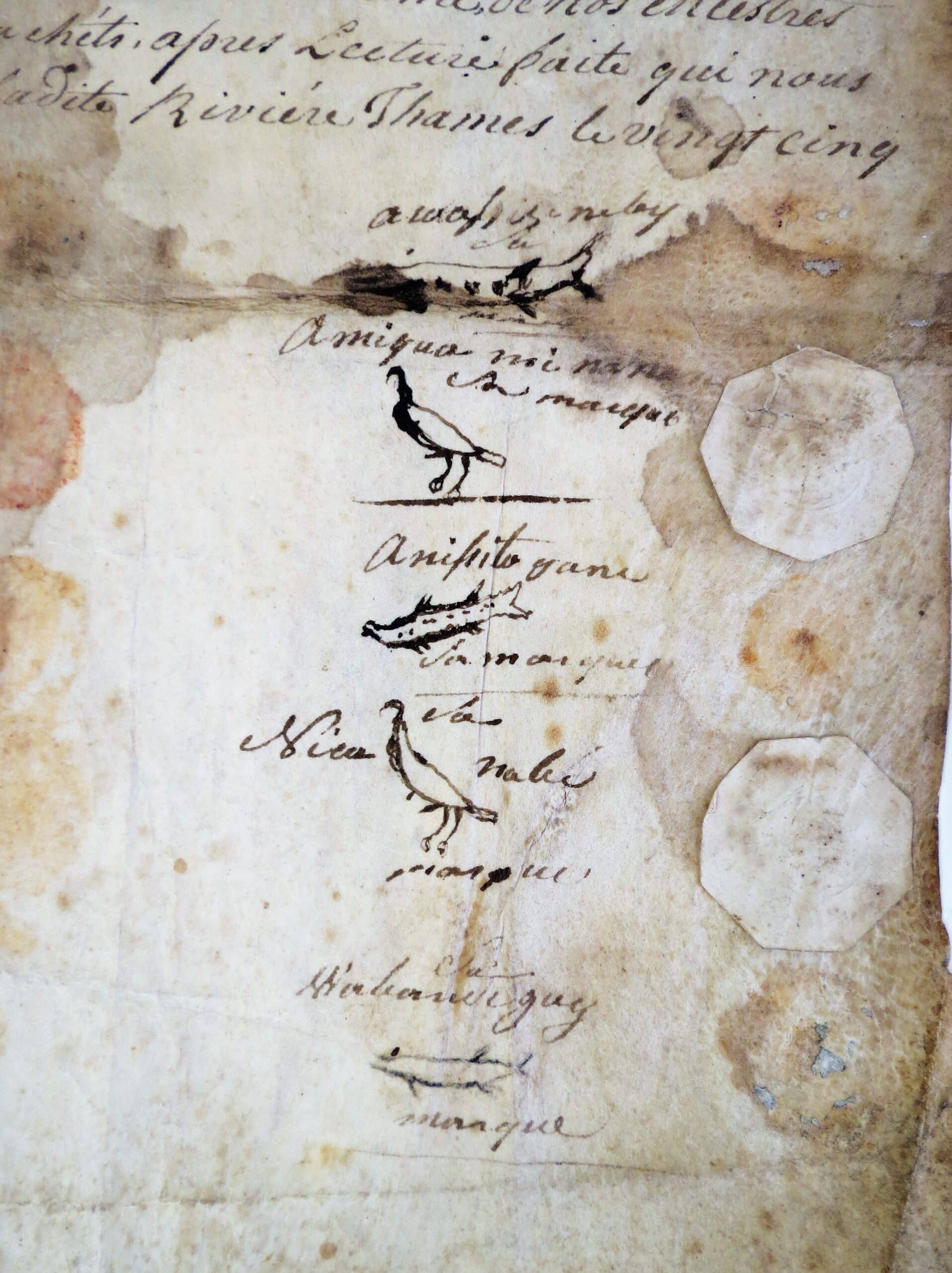

First Nations devised their own distinctive and creative ways to record a significant event like a treaty. One way was the oral transmission from generation to generation by the telling of stories by Elders and other members of the communities. Another way to record a significant event was by weaving a Wampum Belt, used by the Haudenosaunee as a visual record of an agreement. Wampum Belts commemorated events and agreements with other nations, told stories, and described customs, histories or laws. They are not a form of writing. Rather, wampum belts are visual symbols that serve a mnemonic or memory-boosting purpose—a wampum belt triggers and stimulates the reader’s memories of the significance and meaning of the details woven into the belt.

The Wampum Belt pictured on the next page is known as the Kaswentha or Two Row Wampum Belt. This Belt is significant because it embodies the concepts and principles that were the basis of all the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) agreements or treaties

with other nations, including the Dutch, French, and English settlers. The Two Row Wampum Belt is a visual record and statement of the cultural, political, and economic sovereignty maintained by the Haudenosaunee in their treaty with representatives of the Dutch government in 1613 and the basis for later agreements with the Dutch (1645), French (1701) and English (1763-64). The handwritten copy of the Kaswentha was translated from Dutch by Dr. Van Loon.

Learn more about the Two Row Wampum Belt

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

The meaning of the Two Row Wampum Belt is as follows:

We will travel the river together, side by side, but in our own vessel. Neither of us will make compulsory laws nor interfere in the internal affairs of the other. Neither of us will try to steer the other’s vessel.

As long as the Sun shines upon this Earth, that is how long our Agreement will stand—as long as the Water still flows—as long as the Grass grows green at a certain time of the year. We have symbolized this Agreement and it shall be binding forever as long as Mother Earth is still in motion.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Treaties are part of the heritage of First Nations peoples, who entered into a variety of agreements with other First Nations for purposes like sharing lands for hunting and trapping long before the arrival of Europeans in North America. The most famous of these was the Great League of Peace— Kaianere’kó:wa or the Constitution of the Five Nations (the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida and Mohawk people) to live together in peace by forming the Iroquois Confederacy or Haudenosaunee. The agreement was based on democratic ideas that respected the integrity and sovereignty of the member Nations. On October 21, 1988, the 100th Congress of the United States, Resolution 331, acknowledged the contribution of the Iroquois Confederacy to the development of the United States Constitution.

“It is high time that the government stops trying to do things for us and starts doing things with us.”

—Chief Atleo

[BW: Need label for this]

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Beginnings of European-First Nations Interaction

From time immemorial, Indigenous peoples lived and thrived throughout North America. The original peoples had adapted to the diverse landscape, geography and climate of the continent, and evolved complex cultures, languages, customs, religions,

medicinal care and creation stories tied to their strong association and connection with the land. The different Indigenous nations were intimately familiar with the land they inhabited, land that supported them, and which, in turn, they revered and respected. The original inhabitants traded, waged war and made peace with each other, and acquired the skills,

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

knowledge, tools and understandings appropriate to their environment, their customs, history and culture.

From the time of their first arrival in North America, European nations worked out a number of different arrangements with the First Nations. The earliest arrangements were peace and friendship treaties and informal trading agreements between English, French, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish, Basque, and Breton fishermen and First Nations of the east coast (primarily Mi’kmaq and Maliseet). European explorers and settlers, unfamiliar with the different conditions in North America, owed their very existence to the expertise of the Indigenous peoples. However, Europeans sought to increase their wealth and influence in North America and began to establish colonies and settlements which was encouraged by their own countries. By the 1700s both the British and French became the dominant colonial powers.

To strengthen their commercial interests (a significant part of which was the fur trade), the British and the French developed various types of agreements and alliances with First Nations. For example, from 1725 to 1779, the British entered into a number of “Peace and Friendship” treaties with the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy peoples in what are now New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The British colonial administration expected that these treaties would end hostilities between the

British and the First Nations and establish ongoing peaceful relations. Included in these treaties were assurances that First Nations could continue to trade with the British, and hunt, fish, and observe traditional customs and religious practices. No First Nations land was surrendered in these treaties.

The British and French colonial powers expanded their influence from the east coast into the interior of North America by exploiting and developing the long-established First Nations trade routes. What followed were conflicts with each other and First Nations, the building of European forts and posts, and the forging of various alliances and agreements with First Nations.

Military conflicts between the French and British (also involving their First Nations allies) were common, reaching a critical point in 1760. French colonial efforts ended when Montréal, the last French colony on the St. Lawrence River, fell to the British. To consolidate British power, and to ensure peaceful relations with First Nations, the British created a series of treaties between themselves (known as “The Crown”) and First Nations communities.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Later Treaties

In 1763, a document titled the Royal Proclamation contained a number of significant provisions. It integrated the French territories into the new Province of Québec. The Royal Proclamation also specified that future negotiations with First Nations were to be between First Nations and representatives of the British crown, not with private individuals, and that these negotiations would take the form of written treaties. Furthermore, many view the Royal Proclamation as the first legal instrument unilaterally issued by the Crown that recognizes the fundamental rights of First Nations to their lands and resources, and their sovereignty.

A series of treaties were signed after the Royal Proclamation: the Upper Canada Treaties (1764 to 1862) and the Vancouver Island Treaties (1850 to 1854). The American War of Independence and the creation of the United States of America resulted in the British assigning land to a flood of immigrant British loyalists from the new United States of America and to First Nations allies of Britain who lived in the new country during the American War of Independence. The need for more land caused the British to exert greater pressure on First Nations.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

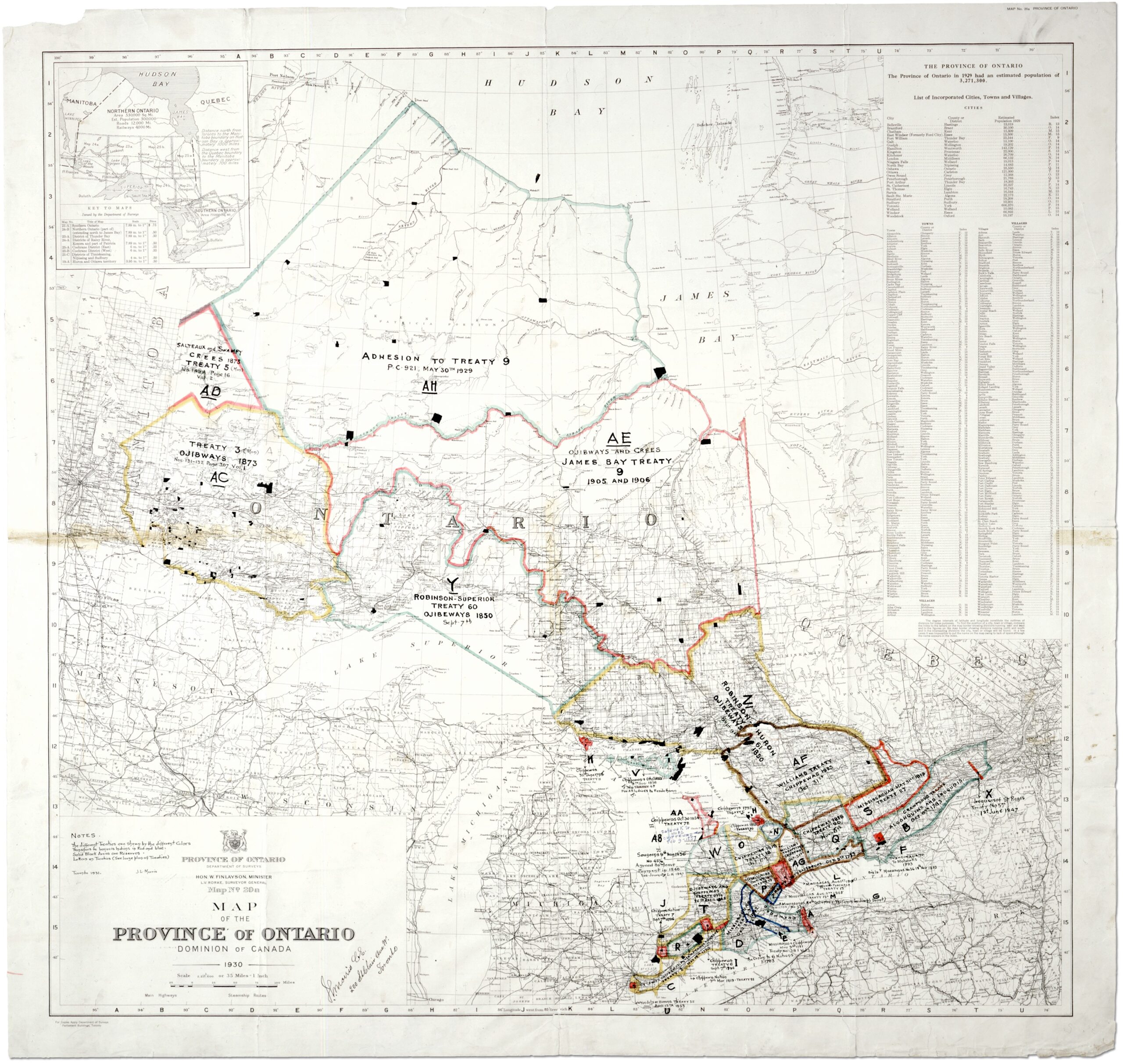

By the 1830s, First Nations found themselves forced into small remnants of their original territories that were economically unsustainable, with limited opportunities for growth, and increasingly losing access to medicinal plants and food, and hunting and fishing grounds. From 1871 on, the Canadian government signed treaties with First Nations for the development of farming and resource exploitation in the west and north of the country. These particular treaties have come to be known as the Numbered Treaties associated with Northern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and parts of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and British Columbia.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

The Numbered Treaties (1-11): 1871-1921

As required by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the British Crown, through their representatives of the Dominion of Canada, were obliged to enter into formal treaty processes before they could expand westward. The British Crown and First Nations interpreted the meaning and intention of treaties in drastically different ways.

The British Crown considered the Numbered Treaties to be an exchange for the surrender of Indigenous Rights and Title to land, so settlers from foreign lands could occupy lands within the colonial territories that the British laid claim to. In return, the British Crown guaranteed First Nations certain Treaty and Inherent Rights in perpetuity.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

First Nations that signed these Numbered Treaties believed they were entering a trust relationship with the British Crown; First Nations were to share and co-exist with settlers from foreign lands. Therefore, First Nations never agreed to the sale of their lands and resources. Instead, they agreed to share their Indigenous lands, to the depth of a plough, as stated in the following quote:

“At the time, the government said that we would live together, that I am not here to take away what you have now…I am here to borrow the land…to the depth of a plough…that is how much I want.”

—Senator Allan Bird, Montreal Lake Cree Nation, Treaty 6

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Based upon First Nations oral histories and written documentation, including that of the actual written text of the Numbered Treaties, First Nations assert that the British Crown made the following promises when the Numbered Treaties were negotiated and signed, which have come to be known as First Nations Treaty and Inherent Rights.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Unceded Territory

The last of the historical treaties were signed in 1923. Government policy moved increasingly towards enfranchisement and laws that would prohibit First Nations sovereignty, including making it a criminal offence for a First Nation to hire a lawyer to pursue land claims settlements.

Consequently, treaties were never concluded with First Nations in some parts of Canada, including most of British Columbia. First Nations without treaties assert their rights to their lands as the land was not ceded to the government.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

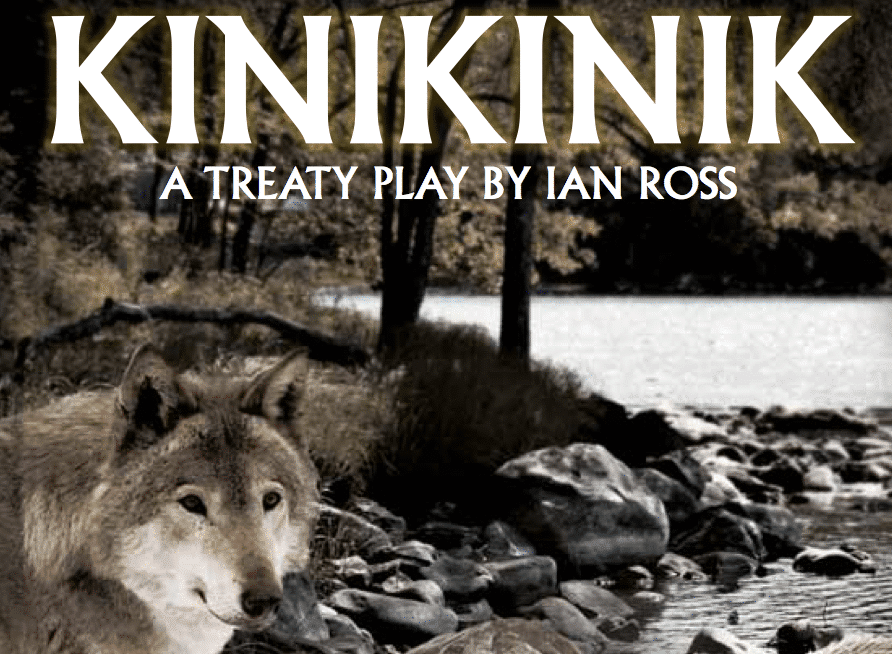

Modern Treaties in Canada: 1975-Present

Modern treaties are also known as comprehensive land claims agreements. A Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples report states that “Treaties are solemn agreements that set out promises, obligations, and benefits for both the Aboriginal peoples and the Crown in right of Canada.”

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Some of Canada's modern Treaties/Comprehensive Land Claims and Self Government Agreements.

Tap the dates for more information:

- James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement and Complementary Agreements (effective date 1977)

- The Northeastern Quebec Agreement

- Labrador Innu Nation Final Agreement

- Quebec Innu-Regroupement Petapan Inc Final Agreement

- The Western Arctic Inuvialuit Final Agreement

- Sechelt Indian Band Self-Government Agreement

- Meadow Lake Final Agreement

- The Gwich’in (Dene/Métis) Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement

- Nunavut Land Claims Agreement

- Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement – Volume I

- Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement – Volume II

- Umbrella Final Agreement between the Government of Canada, the Council for Yukon Indians and the Government of the Yukon

- Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Self-Government Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Champagne and Aishihik First Nations Self-Government Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Teslin Tlingit Council Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Teslin Tlingit Council Self-Government Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation Final Agreement (effective date 1995)

- Nacho Nyak Dun First Nation Self-Government Agreement/ (effective date 1995)

- Nunavut Land Claims Agreement

- Lheidli T’enneh Final Agreement

- Sechelt Final Agreement

- Yekooche Final Agreement

- Fort Frances Chiefs Secretariat Final Agreement

- Deline-Sahtu Dene and Metis Final Agreement

- Anishinabek Nation (Union of Ontario Indians) Final Agreement

- Little Salmon/Carmacks Final Agreement

- Little Salmon/Carmacks Self-Government Agreement

- Selkirk First Nation Final Agreement

- Selkirk First Nation Self Government Agreement

- Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Final Agreement

- Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Self-Government Agreement

- Mohawks of Akwesasne Final Agreement

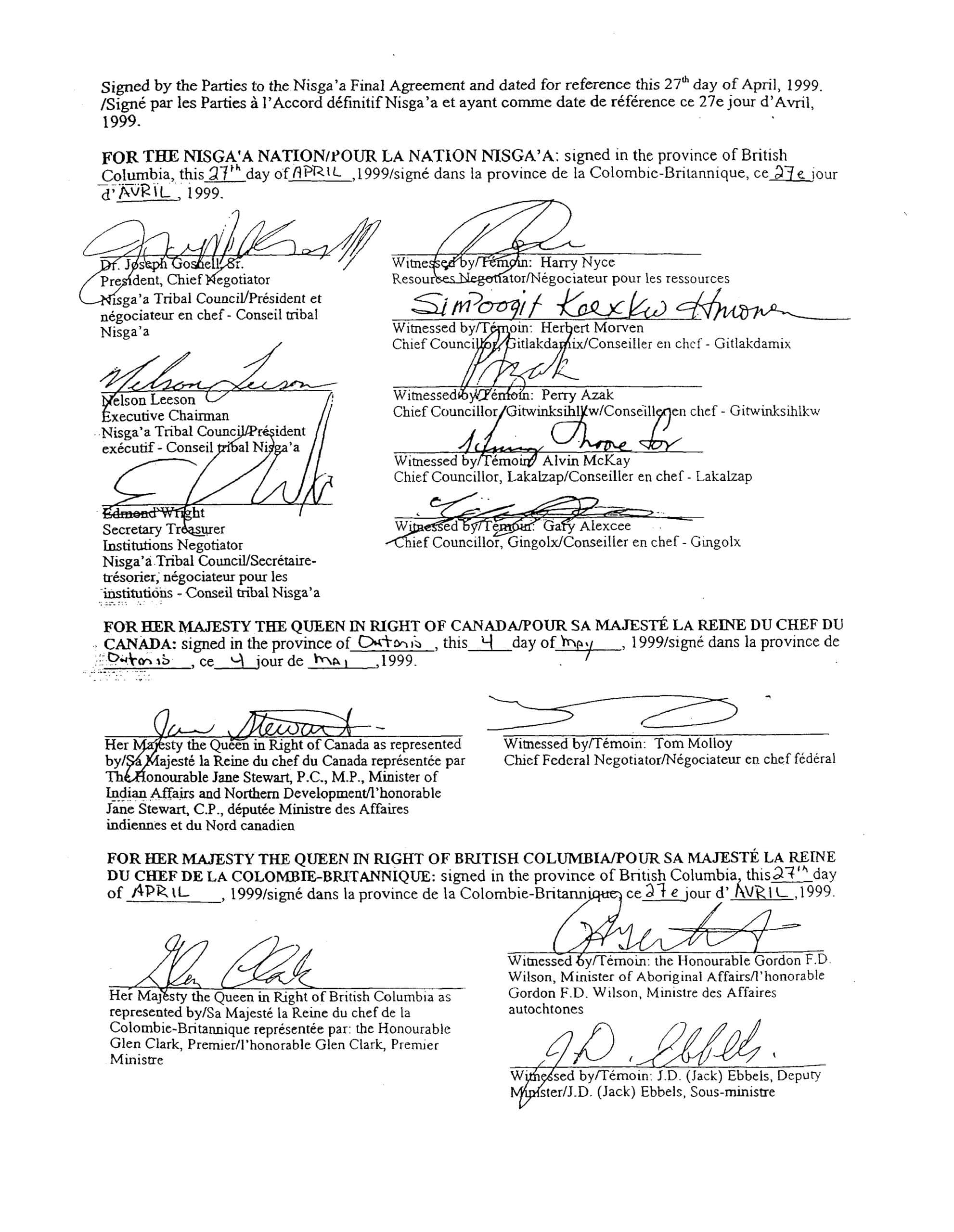

- Nisga’a Final Agreement

- Manitoba Denesuline Negotiations North of 60 Final Agreement

- Athabasca Densuline Negotiations North of 60 Final Agreement

- In-SHUCK-ch Final Agreement

- Ta’an Kwach’an First Nation Final Agreement

- Tlicho Agreement (signed on August 25, 2003)

- Kluane First Nation Final Agreement

- Westbank First Nation Self-Government Agreement

- Miawpukek First Nation of Conne River Final Agreement

- First Nation Education Steering Committee Final Agreement

- Labrador Inuit Land Claim Agreement

- Carcross/Tagish First Nation Final Agreement

- Kwanlin Dun First Nation Final Agreement

- K’omoks First Nation Final Agreement

- Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement

- Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement

- Inuit Transboundary Negotiations in Northern Manitoba Final Agreement

- Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement

- Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Final Agreement

- Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Agreement

- Deline First Nation Final Agreement

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

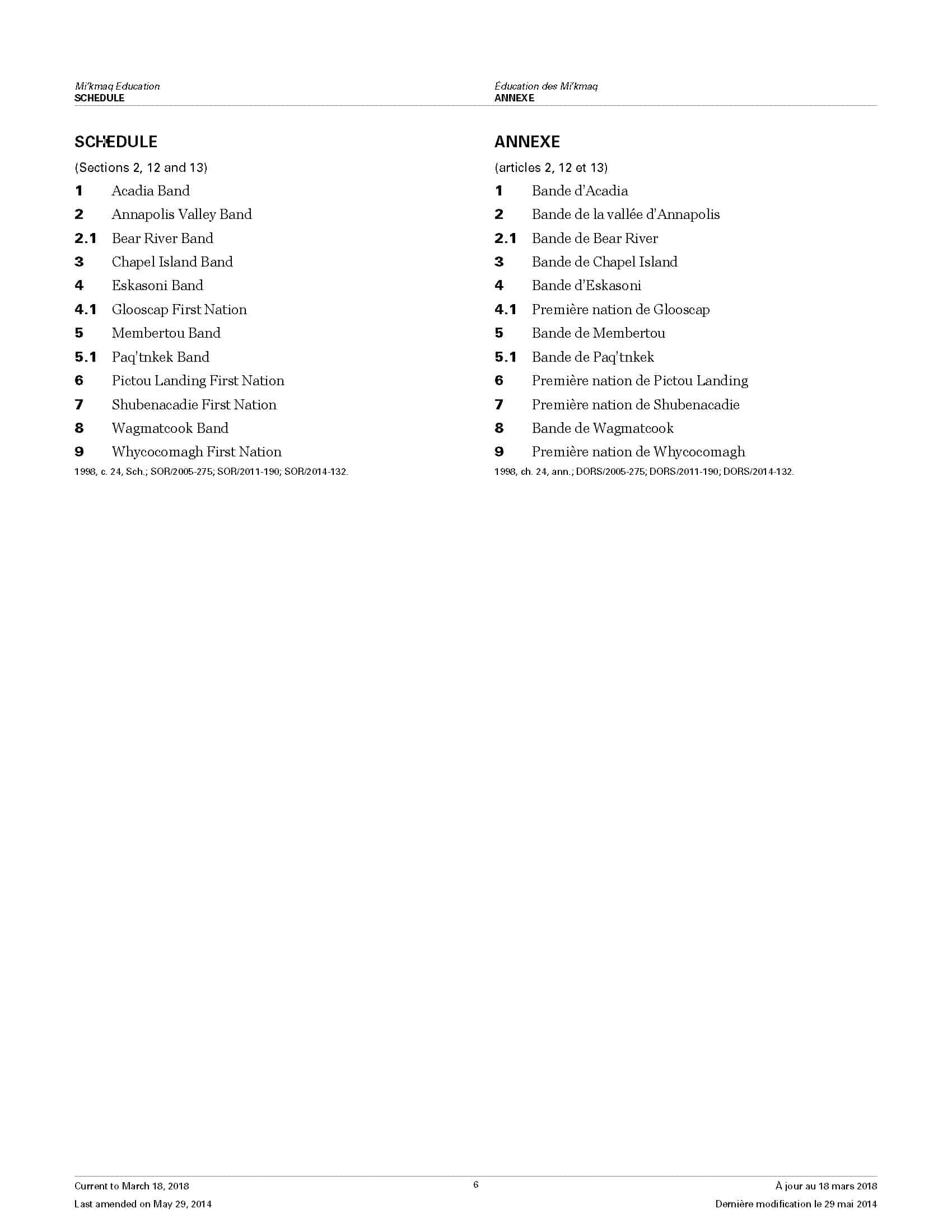

Education Agreements:

2006 – First Nations Jurisdiction over Education in British Columbia Act

1998 – Mi’kmaq Education Act

1997 – Anishinabek Nation (Union of Ontario Indians) Education Final Agreement

For a more comprehensive list of agreements under various stages of negotiation, please visit the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada website.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Interpretations and Perspectives

The history, interpretation and implementation of treaties have been, and continue to be, contentious and controversial.

Critics have made some compelling arguments that all treaties are potentially flawed and subject to re-examination. This quote summarizes some of the complexities of dealing with the content and meaning of treaties and of resolving treaty disputes:

“For an understanding of the relationship between the Treaty Peoples and the Crown of Great Britain and later Canada, one must consider a number of factors beyond the treaty’s written text. First, the written text expresses only the government of Canada’s view of the treaty relationship: it does not embody the negotiated agreement. Even the written versions of treaties have been subject to considerable interpretation, and they may be scantily supported by reports or other information about the treaty negotiations.”

—Sharon H. Venne, “Understanding Treaty 6: An Indigenous Perspective” in M. Asch, ed., Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada (2002)

The Canadians (British) and the First Nations were at the same meetings, listened to the same speeches (translated) and signed the same pieces of paper. Yet they had (and still have) two totally different concepts of what the treaties were about, and what each side was promising. The differences in understanding are rooted in two totally different worldviews, and two totally different concepts of land ownership and two colliding purposes.

Section 2

Law

A number of court cases have provided landmark decisions in cases involving Aboriginal Rights and Title.

“The vote…has paved the way for new rights and new responsibilities. Indians now have a legal voice in the affairs of the province and a right to ask for equality of citizenship. Today the Indian stands as a second-class citizen, robbed even of his native rights… my picture of a full Magna Carta for natives is equality of opportunity in education, in health, in employment and in citizenship.”

—Frank Calder

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

The 1967 Calder case involved Frank Calder and several Nisga’a elders who brought a lawsuit against British Columbia, claiming their land title had been illegally abrogated. Although the judgment wasn’t in the Nisga’a favour, it’s considered a landmark moment for Indigenous land rights because the Supreme Court of Canada cited the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Issued by King George III of England, it decreed that Aboriginal land title in North America existed and would continue until treaty extinguished it, and forbade settlers from acquiring land from Aboriginals, either by purchase or by force.

On June 26, 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Tsilquot’in First Nation, residing in central British Columbia, did possess clear Aboriginal title to around 1800 square kilometres of ancestral land—and that the forestry licences issued to logging companies in the early 1980s had violated the Tsilquot’in right to determine how their lands are used. The case was a triumph for Indigenous rights.

There are five types of challenges with understanding what treaties really mean, largely because of differences in worldviews held by the Europeans and First Nations.

The first challenge has to do with the meaning and symbolism of the word “land.” There is a profound difference between “sharing land” (the view of the First Nations) and “owning land” (the view of the Europeans).

The meaning of “land” to First Nations is expressed in this quote from Canada in the Making:

The concept of land ownership was completely alien to the Native peoples. From an Aboriginal cultural and spiritual perspective, land cannot be bought or sold. They saw themselves as the spiritual guardians of the land, not its actual owners. Land was considered a gift from the Creator or Great Spirit, and its resources were to be used for survival purposes only. Thus, the concept of ‘surrendering’ land was one that caused great confusion within Aboriginal communities…

As stated in http://firstpeoplesofcanada.com/fp_treaties/fp_treaties_two_views.html:

First Nations believed they were merely giving the new settlers the right to use some of their lands for farming. First Nations people are certain they had no thought of giving up all title to their land, nor could they even comprehend the concept of extinguishment of all title and all rights to their land forever.

The second challenge concerns the form or process of the treaties. Europeans used written statements to formalize agreements, while First Nations relied on verbal or oral forms as their “documents.” In signing treaties with Europeans, First Nations were using a foreign medium—a written document—with implications that the First Nations could not possibly have been aware of or understood. As expressed in Treaties & Cultural Change:

First Nations had an oral tradition. They passed down important information by the spoken word during important ceremonies and at celebrations. What was said was what was important to them, not what was written on paper.

Although First Nations had no written tradition, some First Nations had developed the Wampum Belt—a visual form of telling a story, recording an agreement and serving a range of other ceremonial functions.

The third challenge has to do with the relationship of the signers. First Nations saw themselves as sovereign and distinct peoples who were entering a relationship with other sovereign and distinct peoples, the Europeans. From the perspective of the First Nations, there would be respect for the traditions, cultures, religions and customs of both signatories to the Treaties. However, it was clear that the Europeans viewed the Treaties as the beginning of the assimilation of First Nations into the worldview and customs of the Europeans, a position of the European nations that would have profound consequences on the future health, stability, and integrity of First Nations peoples and communities.

The fourth challenge concerns the scope of the Treaties, in what might be termed a literal versus a spirit and intent character. Europeans took a very literal understanding of the Treaties, meaning that the obligations and responsibilities were limited to the terms that were specified and laid out in the Treaties. First Nations, on the other hand, had a wider and broader understanding and perspective of the terms outlined in the Treaties. For First Nations, treaties were only a starting point. First Nations saw verbal obligations, responsibilities or statements made by the original European negotiators as inherent components of the Treaties—honour and honesty were valued. Treaties were seen as living and dynamic agreements that continued to develop and unfold as the circumstances of both signatories changed and evolved.

The fifth challenge has to do with language. Professional, experienced translators know well that serious errors can be made when translating an idea, a statement, even a word, from one language into another. For example, a word in one language may not have a precise counterpart or may have a variety of counterparts in another language. Because of the very nature and complexities of languages, it’s rare for any translation to be absolutely perfect and an exact copy. These potential errors can be magnified when translation is conducted by people who are not trained in the subtleties of languages and who may be unaware of the influence that context can have on translated words, phrases or concepts. The translation minefield can be made even more treacherous when a document is written by only one side and in that side’s language, but must be understood and accepted by someone speaking another language.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

After the creation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867, treaties continued to be signed with First Nations, with the role of the European nations assumed by the Government of Canada. By necessity, this Plain Talk can provide only a brief overview of the topic of treaties by focusing on the nature, history and problems encountered. A huge volume of material is available in hard copy in various archives and on the Internet for people who wish to learn more.

Both Manitoba and Saskatchewan have produced excellent resources devoted entirely to the critical topic of treaties:

The Manitoba Treaty Education Initiative Tool Kit, developed by the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba (TRCM); and the Saskatchewan Treaty Kit K-12, developed by the Office of the Treaty Commissioner. Both resources should be consulted for definitive and extensive coverage of treaties and treaty relationships.

The theatre offers an excellent arena for exploring delicate and controversial issues. Governor General Award-winning playwright Ian Ross has written a wonderful, funny, and insightful play about treaties. Titled Kinikinik, the play explores the issues concerning treaties. The playwright uses a willow branch as a symbol for land. Two characters, a Wolf and a Beaver, compete for possession or ownership of the willow.

A third character, a Turtle, leads the Wolf and Beaver through the discovery that it’s not easy to resolve possession of the willow. The characters discover that a verbal agreement might not be sufficient. They also discover that a written agreement like a treaty could be unfair if the agreement is created by only one side and in language that might not be completely understood by the other party. Whether read out loud by a group, or performed by an amateur or professional theatre group, Kinikinik is a powerful exploration of the intricacies of the creation, implementation, and interpretation of treaties.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Treaties, as agreements between sovereign entities like nations, invariably establish a relationship between the nations. The phrase “we are all treaty people” springs from the work of the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba. We are all treaty people is a concise statement that both First Nations and Canadians are integral partners in every treaty, and that we all have the responsibility to ensure that treaties be honoured and respected. It is unfortunate that Canadian governments have consistently failed First Nations by ignoring or not fulfilling their treaty commitments. By acknowledging and implementing its treaty obligations, Canadian governments could make significant steps in reversing and resolving a range of inequities endured by First Nations. This is especially deplorable given Canada’s endorsement of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN Declaration)in 2010 and 2016. (More information on the UN Declaration can be found in the Tool Kit.)

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Grand Council Chief Madahbee of the Anishinabek Nation, in a letter to the Prime Minister of Canada, has expressed his dismay at the federal government’s continuing efforts to erode First Nations treaty and inherent rights.

Read Grand Council Chief Madahbee letter to the

Prime Minister of Canada or listen to a recording below:

Section 2

Chief Atleo Observations

Assembly of First Nations former National Chief Atleo offers some observations about treaties and treaty rights.

“I invite all of you to join with us, with First Nations, on this new national dream towards a better, stronger Canada. We can create a brighter future, in the same way that our ancestors came together with a vision of a nation founded on mutual respect, partnership and sharing.”

— Chief Atleo

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

(To view a complete version of Chief Atleo’s

observations visit the the iTunes U Tool Kit course.)

Recognizing and implementing Aboriginal and Treaty rights takes us back to the very founding of this country—a country founded on our lands and politically on peaceful agreements based on respect, recognition, sharing and partnership.

Since 1982, successive governments have shown little interest in the real and hard work of reconciliation. There has been talk, but we know the equation of empty initiatives: talk minus action equals zero.

First Nations though are not standing still—are not waiting. We’re taking action. For decades now we’ve been putting forward positive plans for progress and change, plans aimed at breathing life into the promises we made to one another and plans that will ensure a better future for our children.

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

Chief Atleo on the path ahead

Tap the dates for more information:

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

We need approaches that implement First Nation Treaty and inherent rights. On a Treaty-by-Treaty or nation-to nation basis, we must set out a new course—one of commitment, of dedicated energy and of focus to achieve resolution. This new course would give life to a lasting relationship of mutual respect and prosperity.

Canada continues to not even have a policy or approach to implement or monitor its treaty relationship with First Nations, even though the Treaties are the founding documents of this country. This is essential and a requirement for the implementation of the spirit and intent of the Treaties.

By “spirit and intent,” I am referring to the First Nations understanding of the Treaties, and respecting and recognizing that perspective.

It’s time for change. Now is our time. First Nations are pushing and pursuing every opportunity for cooperation. We know there are ways we can work together that benefit all and honour the promise we made to one another.

First Nations want to be full partners in designing a collective future—for our communities and the country as a whole.

I invite all of you to join with us, with First Nations, on this new national dream towards a better, stronger Canada. We can create a brighter future, in the same way that our ancestors came together with a vision of a nation founded on mutual respect, partnership and sharing.

Section 35 and other steps have set our path and this is a tremendous advantage—the road ahead is long and it is difficult—but it is a road we must travel together. When we think again of Bear, we realize that it is story principally about achieving relationship-success—a story of reconciliation with tremendous economic and sustainability benefits for all involved. Its wisdom speaks powerfully to us today and of our work together.

I’ll close by recalling the words of Chief Justice Lamer, that “we are all here to stay.” I would add to those wise words that we are all in this together and together we can succeed.

Kleco, Kleco!

National Chief Shawn Atleo

Chapter 2Treaties

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

References

Borrows, John. Canada’s Indigenous Constitution. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Borrows, John “Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self-Government,” in Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada, ed. Michael Asch. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997, 155.

Canada in the Making: Aboriginals: Treaties & Relations: http://www.canadiana.ca/citm/themes/aboriginals1_e.html

Canada. Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. (May 2008). Honouring the Spirit of Modern Treaties: Closing the Loopholes, Special Study on the implementation of comprehensive land claims in Canada, Interim Report. www.senate-senat.ca

First Nations in Canada: http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1307460755710/1307460872523

First Nations Treaties in Canada: http://suite101.com/article/first-nations-treaties-in-canada-a103415

Kinikinik: A Treaty Play by Ian Ross, Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba: 2010.

Prince Albert Grand Council. eCulture: http://eculture.pagc.sk.ca/eculture.php?pid=Overview&tp=slnk&language=&ver=

The Manitoba Treaty Education Initiative Tool Kit, developed by the Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba (TRCM).

The Saskatchewan Treaty Kit K-12, developed by the Office of the Treaty Commissioner.

Treaties & Cultural Change: http://firstpeoplesofcanada.com/fp_treaties/fp_treaties_two_views.html

Treaties with Aboriginal People in Canada: http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032291/1100100032292

Image Sources

pg.3 The Hiawatha Wampum Belt,

or Dish with One Spoon.

Wabano House, Ottawa. [ca. 2017]

pg.5 The Hiawatha Wampum.

Photographer Mark D. Read [ca. 2018]

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

pg.6 A view of the ruins of the fort at Cataraqui

taken in June, 1783.

Artist and surveyor, James Peachy

Kingston Picture Collection/Queen’s University Archives

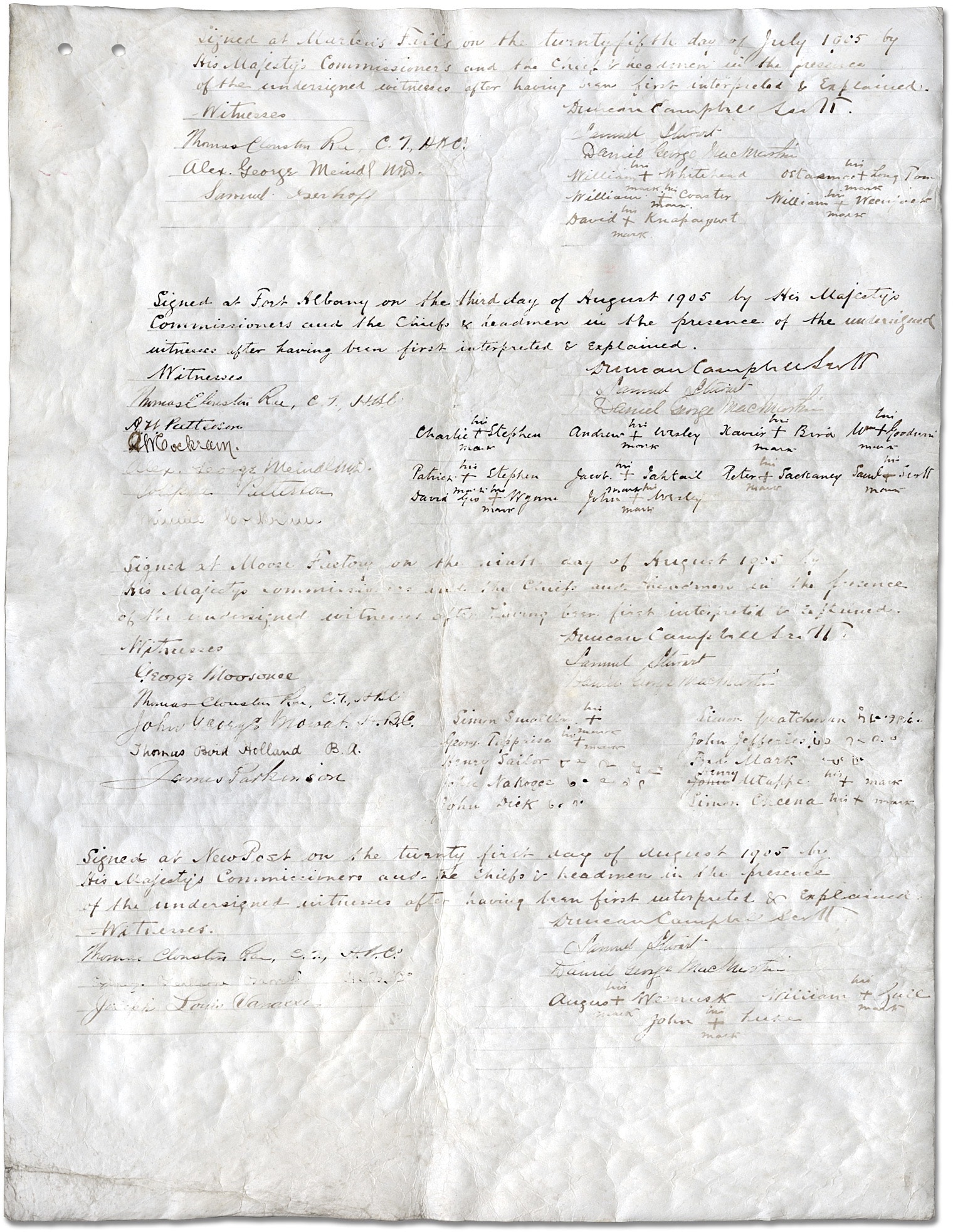

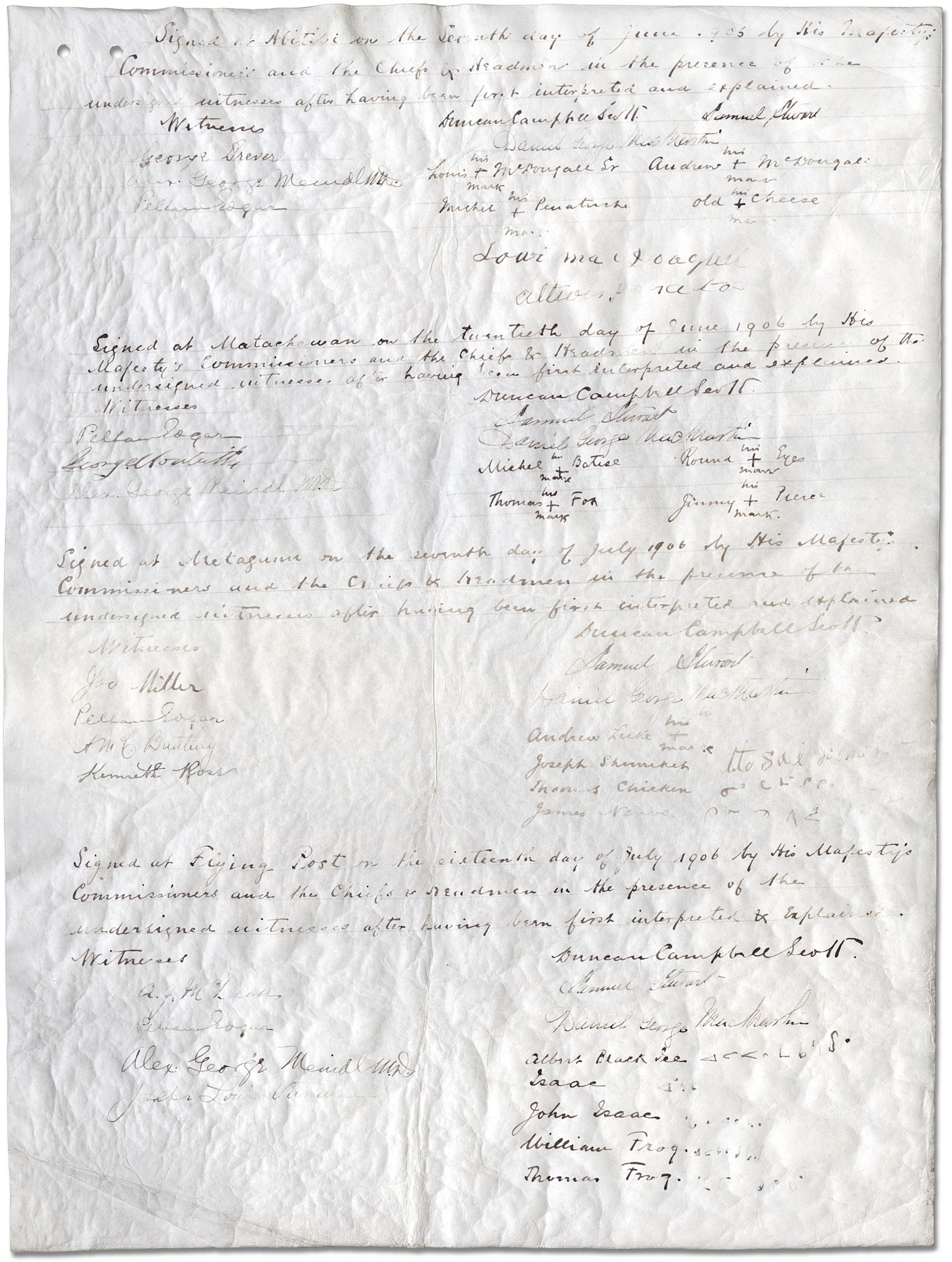

pg.8 Chiefs Signatures on the Treaty with the Chippewa, October 4, 1842.

Photographer Mark D. Read, [ca. 2018]

Queen’s University Archives

pg.9 Preparing the feast to be held after the James Bay Treaty signing ceremony, Osnaburgh House

Photographer unknown [July 12, 1905]

Duncan Campbell Scott fonds/Archives of Ontario

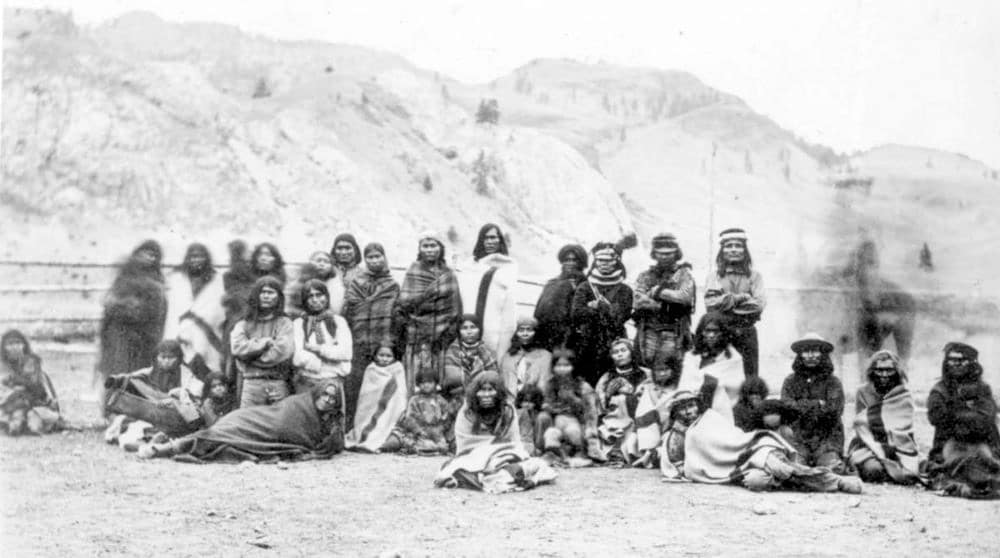

pg.10 Women and children [of Brunswick House First Nation] at the feast during Treaty 9 payment ceremony at [the Hudson’s Bay Company Post called] New Brunswick House, Ontario.

Photographer Duncan Campbell Scott

[ca. July 25, 1906]

Library and Archives Canada

pg.11 Map No. 20a. Ontario: Department of Surveys

J. L. Morris fonds [1931]

Archives of Ontario

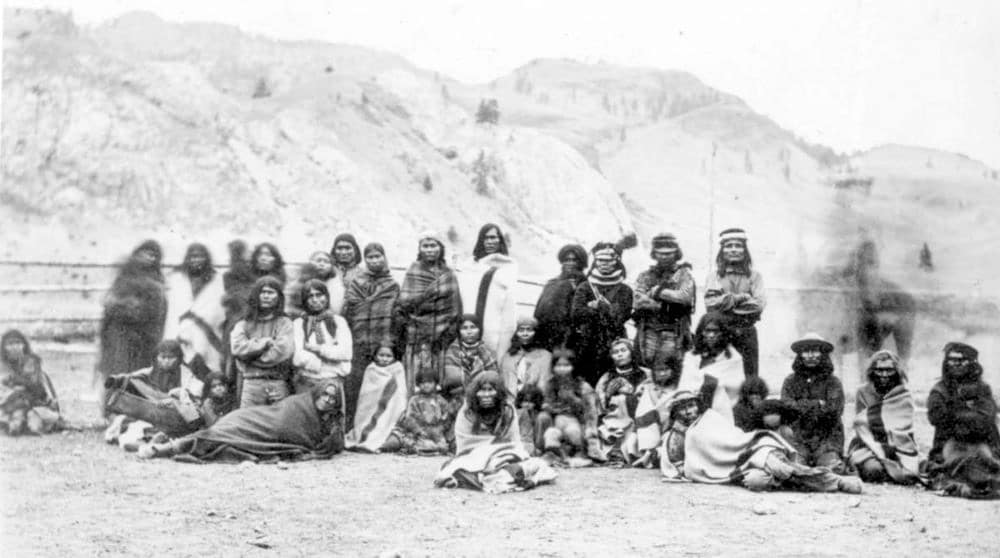

pg.14 British Columbian Siwashes. Lilloett,

[Lillooett] B.C.

Frederick Dally Fonds [ca. 1866-1870]

Royal British Columbia Museum Archives

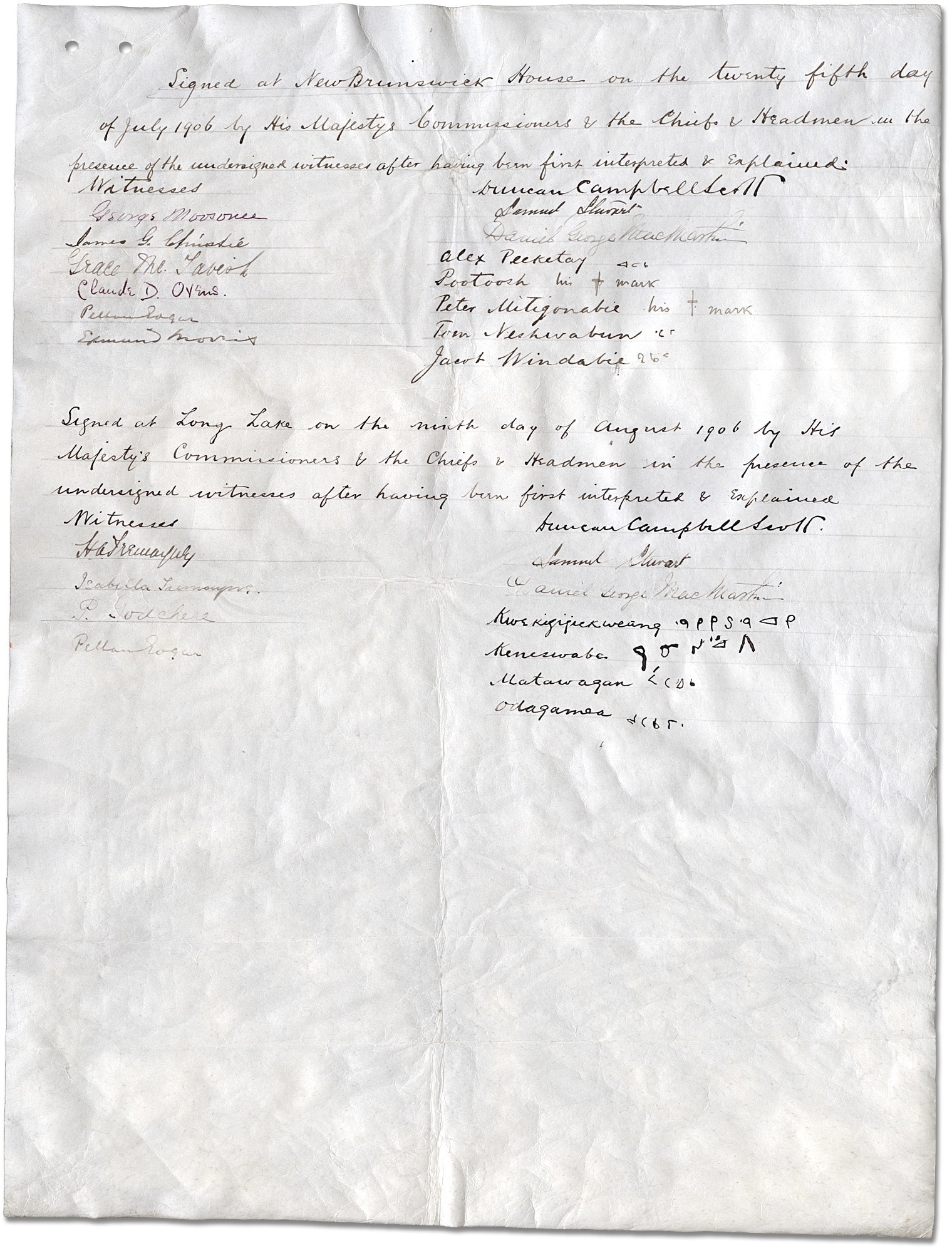

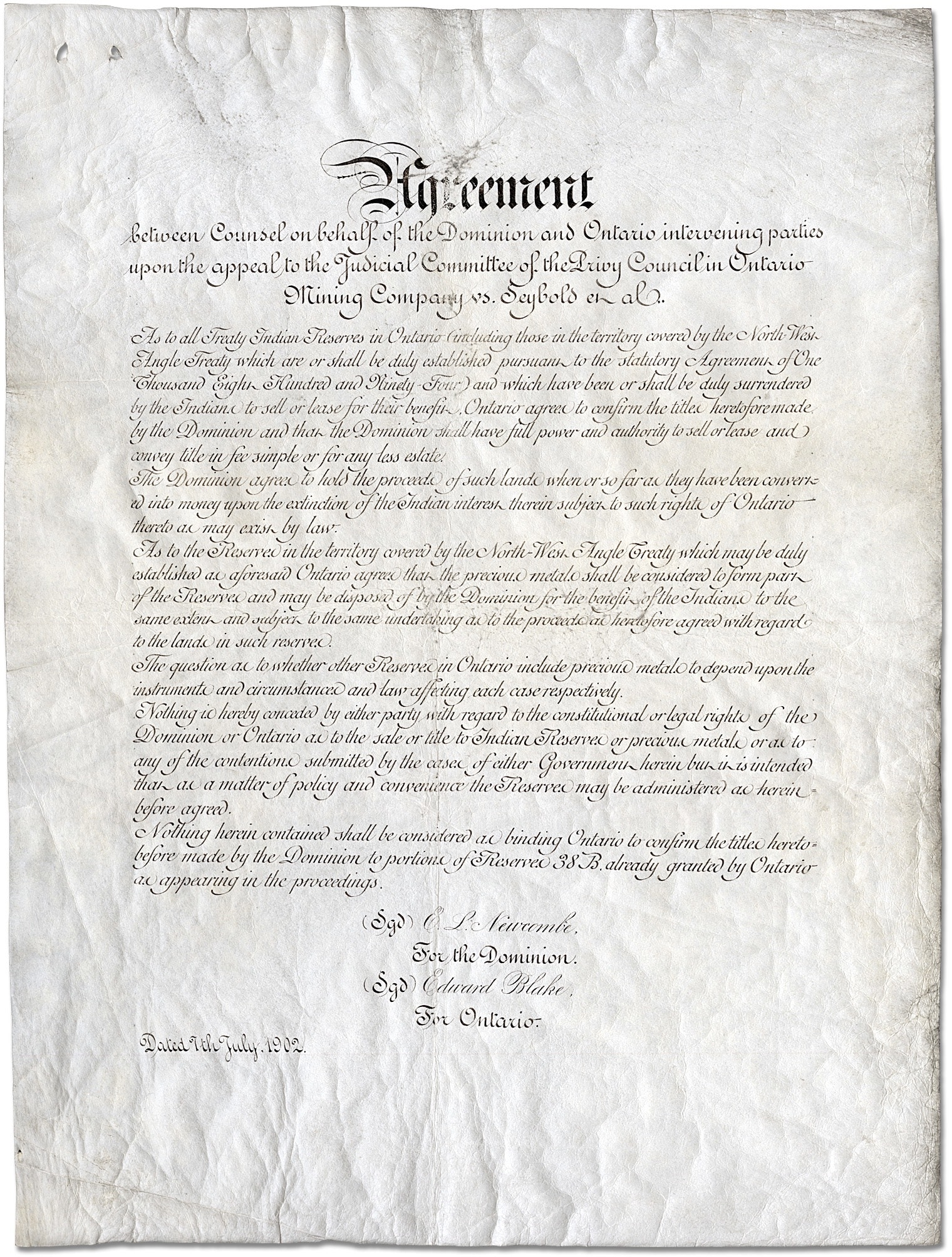

pg.18 James Bay Treaty (Treaty No. 9) [pages 1-7]

Archives of Ontario

pg.19 Dr. Frank Calder, Hubert Doolan, Senator Guy Williams, Eli Gosnell, unknown, William McKay, and James Gosnell. [ca. 1973]

source: http://www.nisgaanation.ca/nisga%E2%80%99-land-question-0

pg.21 Kinikinik, A Treaty Play by Ian Ross.

Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba

[ca. 2010]

pg.23 Grand Chief Pat Madahbee.

The Manitoulin Expositor, file photo.

source: http://www.manitoulin.ca/2016/04/13/grand-chief-pat-madahbee- meets-pm/

pg.24 Crown-First Nations Gathering, with the late Elder Bertha Commonda smudging Prime Minister Harper along with National Chief Shawn Atleo and Governor General David Johnston.

Photographer Fred Carroll [ca. January 24, 2012]

Plain Talk 4 | Treaties

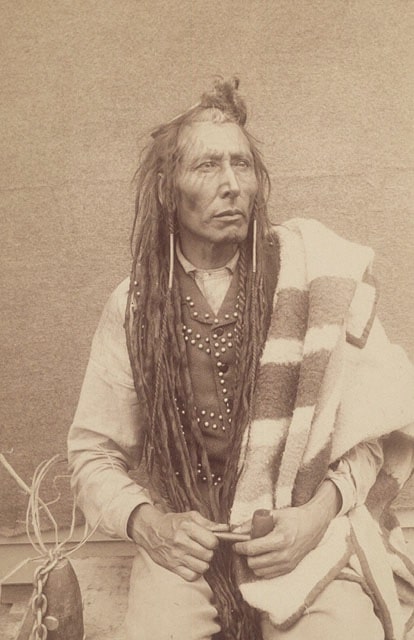

pg.25 No.4, Cree Chief Poundmaker (1842?-1886),

after his arrest in June 1885, Regina, Saskatchewan. Library and Archives Canada