Plain Talk 6Residential Institutions (Schools)

Chapter 1Residential Institutions (Schools)

This chapter will provide information on the origin of Residential Institutions, impacts on students and communities, and action taken by Canadian and First Nations governments to begin the process of reconciliation.

Section 1

What are Residential Institutions?

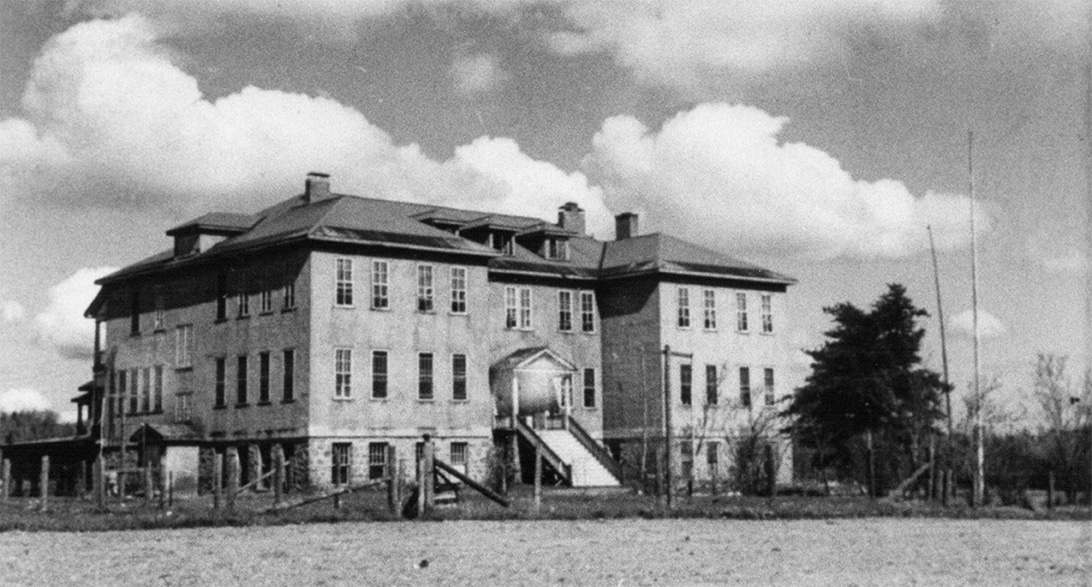

Residential Institutions were boarding schools for Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) children and youth, financed by the federal government but staffed and run by several Christian religious institutions— the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Methodist Churches. Children were separated from their families and communities, sometimes by force, and lived in and attended classes at the schools for most of the year. Often the Residential Institutions were located far from the students’ home communities.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Why We Use the Word ‘Institutions’

As documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for many, Residential and Day Institutions were places of abuse and neglect. While this book uses the term ‘Residential Institutions’ except when referring to proper names, Survivors, families, and First Nations should be empowered to use the words that reflect their lived experience.

“It’s very clear that genocide did happen in Canada and that these were not schools.

These were institutions of assimilation

and genocide.”

—AFN National Chief RoseAnne Archibald

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of one former student's story.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Residential Institutions Timeline

-

1620-1680

Boarding schools are established for Indian youth by the Récollets, a French order in New France, and later the Jesuits and the female order of the Ursulines. This form of schooling lasts until the 1680s.

-

-

1820

Early church institutions (schools) are run by Protestants, Catholics, Anglicans and Methodists.

-

-

January 26, 1831

The Mohawk Institute opens: The first Residential Institution, The Mohawk Institute near what is now Brantford, ON, opens.

-

-

1847

Egerton Ryerson produces a study of native education at the request of the assistant superintendent General of Indian Affairs. His findings become the model for future Indian Residential Institutions. Ryerson recommends that domestic education and religious instruction is the best model for the Indian population. The recommended focus is on agricultural training and government funding will be awarded through inspections and reports.

-

-

1860

Indian Affairs is transferred from the Imperial Government to the Province of Canada. This is after the Imperial Goverment shifts its policy from fostering the autonomy of native populations through industry to assimilating them through education.

-

-

April 12, 1876

The Indian Act is enacted: The Indian Act provides a single coordinated policy to assimilate First Nations peoples into white, Christian culture.

-

-

July 1, 1883

Federal government authorizes Residential Institutions: Then-Prime Minister Sir John A Macdonald authorizes the creation of the Residential Institution system to assimilate First Nations children to white, Christian culture.

-

-

April 1, 1920

Residential Institutions mandatory: Amendments to the Indian Act make it mandatory for First Nations children ages 7 to 16 years to attend Residential Institutions.

-

-

October 3, 1966

Chanie Wenjack dies: Chanie Wenjack, 12, dies after running away from Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School. His death leads to the first official inquiry into the treatment of children at residential institutions.

-

-

1974

The aboriginal education system sees an increase in the number of native employees in the school system. Over 34 percent of staff members have Indian status. This is after the government gives control of the Indian education program to band councils and Indian education committees.

-

-

1975

A provincial Task Force on the Educational Needs of Native Peoples hears recommendations from native representatives to increase language and cultural programs and improve funding for native control of education. Also, a Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development publication reports that 174 federal and 34 provincial schools offer language programs in 23 native languages.

-

-

1979

15 Residential Institutions are still operating in Canada. The Department of Indian Affairs evaluates the Institutions and creates a series of initiatives. Among them is a plan to make the school administration more culturally aware of the needs of Indigenous students.

-

-

1989

Non-Indigenous orphans at Mount Cashel Orphanage in Newfoundland make allegations of sexual abuse by Christian Brothers at the school. The case paves the way for litigation for residential school victims.

-

-

October 30, 1990

Gordon’s IRS closes: The last federally operated Residential Institution, Gordon’s Indian Residential School, in Punnichy, SK, closes.

-

November 1996

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, or RCAP, issues its final report. One entire chapter is dedicated to Residential Institutions. The 4,000-page document makes 440 recommendations calling for changes in the relationship between aboriginals, non-aboriginals and governments in Canada. The Gordon Residential School, the last federally run facility, closes in Sakatchewan.

-

-

1991

The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate offers an apology to Canada’s First Nations Peoples.

-

-

1993

The Anglican Church offers an apology to Canada’s First Nations people.

-

-

1994

The Presbyterian Church offers a confession to Canada’s First Nations people.

-

-

October 3, 1966

Chanie Wenjack dies: Chanie Wenjack, 12, dies after running away from Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School. His death leads to the first official inquiry into the treatment of children at residential institutions.

-

-

1997

Phil Fontaine is elected National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, a national advocacy organization that works to advance the collective aspirations of First Nations individuals and communities across Canada on matters of national or international nature and concern.

-

-

January 7, 1998

The Government of Canada unveils Gathering Strength: Canada’s Aboriginal Action Plan, a long-term, broad-based policy approach in response to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. It includes the Statement of Reconciliation: Learning from the Past, in which the Goverment of Canada recognizes and apologizes to those who experienced physical and sexual abuse at Indian Residential Institutions and acknowledges its role in the development and administration of Residential Institutions.

- St. Michael’s Indian Residential Institution, the last band-run institution, closes. The United Church’s General Council Executive offers a second apology to the First Nations Peoples of Canada for the abuse incurred at Residential Institutions. The litigation list naming the Government of Canada and major Church denominations grows to 7.500.

-

-

2001

Canadian government begins negotiations with the Anglican, Catholic, United,and Presbyterian churches to design a compensation plan. By October, the government agrees to pay 70 percent of settlement to former students with validated claims. By December, the Anglican Diocese of Cariboo in British Columbia declares bankruptcy, saying it can no longer pay claims related to residential school lawsuits.

-

-

December 12, 2002

Presbyterian Church settles Indian Residential Institutions compensation. It is the second of four churches involved in running Indian Residential Institutions that has initiated an Agreement-in-Principle with the federal government to share compensation for former students claiming sexual and physical abuse.

-

-

March 11, 2003

Ralph Goodale, minister responsible for the Indian Residential Institutions resolution, and leaders of the Anglican Church from across Canada ratify an agreement to compensate victims with valid claims of sexual and physical abuse at Anglican-run Residential Schools. Together, they agree the Government of Canada will pay 70 percent of the compensation and the Anglican Church of Canada will pay 30 per cent, to a maximum of $25 million.

-

-

November 26, 2004

AFN Publishes Report: Report on Canada’s Dispute Resolution Plan to Compensate for Abuses in Indian Residential Schools stresses the need for a comprehensive approach including compensation, truth-telling, healing and public education.

-

-

May 30, 2005

The federal government appoints the Honourable Frank Iacobucci as the government’s representative to lead discussions toward a fair and lasting resolution of the legacy of Indian Residential Institutions.

-

October 21, 2005

The Supreme Court of Canada rules that the federal government cannot be held fully liable for damages suffered by students abused at a church-run Institution on Vancouver Island. The United Church carried out most of the day-to-day operations at Port Alberni Indian Residential Institution, where six aboriginal students claimed they were abused by a dormitory supervisor from the 1940’s to the 1960s. The court ruled the church was responsible for 24 per cent of the liability.

-

November 23, 2005

Ottawa announces a $2 billion compensation package for aboriginal people who were forced to attend Residential Institutions. Details of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement include an initial payout for each person who attended a Residential Institution of $10,000, plus $3,000 per year. Approximately 86,000 people are eligible for compensation.

-

-

May 8, 2006

IRSSA signed: The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement establishes a $1.9 billion fund for survivors.

-

December 21, 2006

The $2-billion compensation package for aboriginal people who were forced to attend residential schools is approved by the Nunavut Court of Justice, the eighth of nine courts that must give it the nod before it goes ahead. (A court in the Northwest Territories is the last to give approval in January 2007.)

- However, the class-action deal—one of the most complicated in Canadian history—was effectively settled by December 15, 2006, when documents were released that said the deal had been approved by seven courts: in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan, and the Yukon. The average payout is expected to be in the vicinity of $25,000. Those who suffered physical or sexual abuse may be entitled to settlements up to $275, 000.

-

-

January 26, 2007

Courts certify Class Actions: Nine courts certify class actions and approved terms of Indian Residential Schools Settlement (IRSSA) settlement.

-

September 19, 2007

A landmark compensation deal for former residential school students comes into effect, ending what Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine called a 150-year “journey of tears, hardship, and pain—but also of tremendous struggle and accomplishment.” The federal government-approved agreement will provide nearly $2 billion to the former students who had attended 130 schools. Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl said he hoped the money would “close this sad chapter of history in Canada.”

-

-

April 28, 2008

Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl announces that Justice Harry LaForme, a member of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation in southern Ontario, will chair the commission that Ottawa promised as part of the settlement with former students of residential schools. At the ceremony, LaForme paid homage to the estimated 90,000 living survivors of residential schools. “your pain, your courage, your perseverance, and your profound commitment to the truth made this commission a reality,” he said.

-

June 1, 2008

TRC is established: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins its work, investigating the origin, purposes and effects of Residential Institutions. For the next six years, the TRC travels across Canada, hearing from more than 6,500 witnesses.

June 11, 2008

Federal apology: Then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper, on behalf of the Government of Canada, formally apologizes to those sent to Residential Institutions, their families and communities.

-

October 20, 2008

Justice Harry LaForme resigns as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for residential schools. In a letter to Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl, LaForme says the commission is on the verge of paralysis because the panel’s two commissioners, Claudette Dumont-Smith and Jane Brewin Morley, do not accept his authority and leadership.

November 5, 2008

Former Supreme Court of Canada justice Frank Iacobucci, appointed in 2005 as the federal government’s representative to lead discussions toward a fair and lasting resolution of the legacy of Indian residential schools, agrees to mediate negotiations aimed at getting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission back on its feet.

-

-

January 30, 2009

Two of the three commissioners on the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Claudette Dumont-Smith and Jane Brewin Morley, announce that they will step down effective June 1.

April 29, 2009

Pope Benedict XVI expresses sorrow: His Holiness expresses sorrow to a delegation from the AFN for Residential Institution abuse suffered at institutions run by the Roman Catholic Church.

-

June 10, 2009

Indian Affairs Minister chuck Strahl announces the appointment of Judge Murray Sinclair, an aboriginal justice from Manitoba, as chief commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for residential schools. Marie Wilson, a senior executive with the N.W.T. Workers’ Safety and Compensation commission, and Wilton Littlechild, Alberta regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations, are also appointed commissioners.

September 21, 2009

Justice Murray Sinclair says he’ll have to work hard to restore the commission’s credibility. Sinclair says people lost some faith in the commission after infighting forced the resignation of the former chairman and commissioners.

-

October 15, 2009

Gov. Gen. Michaëlle Jean relaunches the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission in an emotional ceremony at Rideau Hall. “When the present does not recognize the wrongs of the past, the future takes its revenge,” Jean tells an audience that included residential school survivors. “For that reason, we must never, never turn awat from the opportunity of confronting history together—the opportunity to right a historical wrong.”

December 30, 2009

Canada’s residential schools commission is settling in to its new home—and name—in Winnipeg. New chief commissioner Justice Murray Sinclair moved the headquarters of the commission from Ottawa to Winnipeg. The commission has also changed its name to the Truth and Reconciliation Canada (TRC).

-

-

March 2, 2010

Investigations into cases of students who died or went missing while attending the Government of Canada’s Residential Institutions are a priority for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), says the group’s new research director.

March 19, 2010

Survivors of abuse at Residential Institutions are fearing the end of federal funding on March 31 for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, a nationwide network of community-based healing initiatives. The federal government did not renew its funding for the foundation (AHF), which serves 134 community-based healing programs.

-

April 8, 2010

With the simple cutting of a ribbon, Canada’s Truth an Reconciliation Commission officially opens its headquarters in Winnipeg, two years after it was first created.

April 16, 2010

Thousands of aboriginal Residential Institution survivors meet in Winnipeg for the first national event of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

-

June 21, 2010

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission is pleased with the outcome of its first national event in Winnipeg, despite receiving a smaller number of survivor statements than hoped.

November 12, 2010

The Government of Canada announces it will endorse the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a non-binding document that describes the individual and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples around the world. The Truth and Reconciliation Committee hails the decision as a step towards making amends.

-

-

March 14, 2011

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins three months of hearings in 19 northern communities in the lead up to its second national event, which will be held in Inuvik, N.W.T. between June 28 and July 1.

-

-

December 15, 2015

TRC issues its final report: In addition to its final, seven-volume report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission releases 94 Calls to Action to address the multi-generational impacts of Residential Institutions.

-

-

June 3, 2019

MMIWG Inquiry releases final report: The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls identifies colonial structures, including Residential Institutions, as the root of acts of violence and genocide against women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA+ peoples.

-

-

May 27, 2021

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc: Announces that the remains of 215 children were confirmed at the former Kamloops Residential School.

June 23, 2021

Cowessess First Nation: Announces that the remains of 751 children have been discovered near the former Marieval Indian Residential School.

-

June 30, 2021

Lower Kootenay Band: Lower Kootenay Band announces that a search using ground-penetrating radar has found 182 sets of human remains in unmarked graves outside St. Eugene’s Mission School.

July 13, 2021

Penelakut Tribe: The Penelakut Tribe announces in an online newsletter that more than 160 unmarked and undocumented graves have been found at the former Kuper Island Industrial School site near Chemainus, B.C.

-

September 24, 2021

Federal Court approves Indian Residential Schools Day Scholars settlement: The settlement provides compensation to claimants for harms suffered while attending Residential Institutions as ‘Day Scholars’.

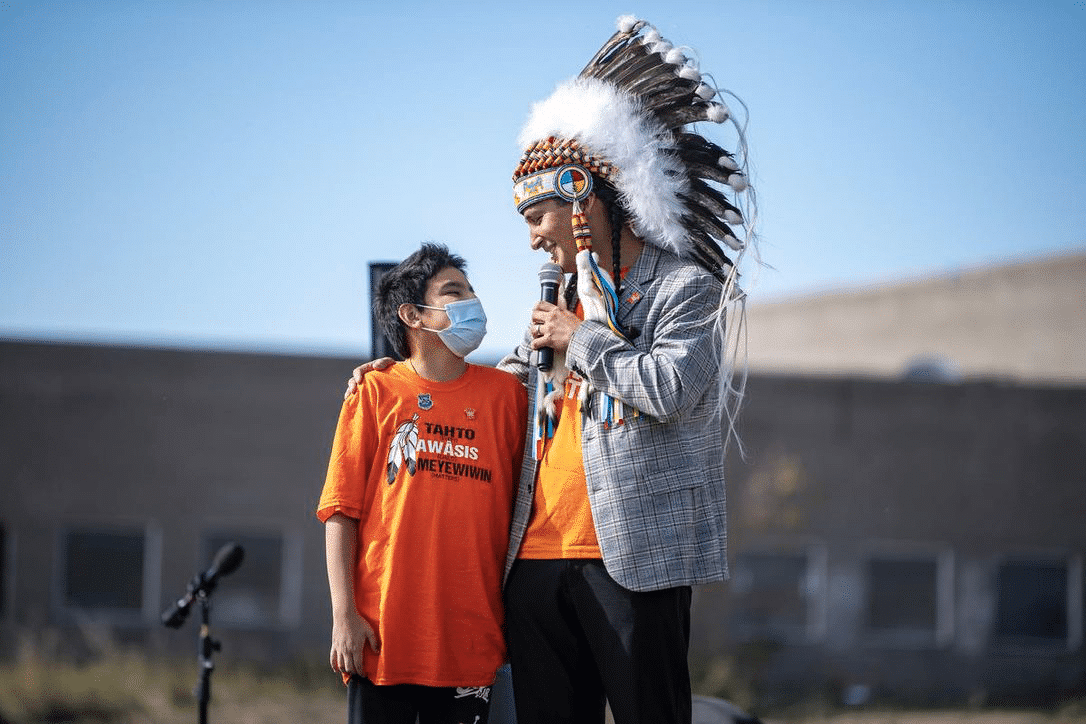

September 30, 2021

First National Day for Truth and Reconciliation: Known as Orange Shirt Day since 2013, September 30 is a day to honour the children who died while attending Residential Institutions, Survivors, families and communities.

-

-

April 1, 2022

Pope Francis apologizes to Indigenous Delegation: The Pope apologizes to First Nations, Inuit and Métis members of an Indigenous delegation during their visit to the Vatican.

May 13, 2022

Pope Francis trip to Canada announced: The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops announces His Holiness will visit Canada July 24 to 29, 2022.

-

July 24, 2022

Papal visit to Canada: Pope Francis visits Canada with stops in Edmonton, Quebec City and Iqaluit, delivering an apology in Maskwacis, Alberta near the site of the former Ermineskin Residential School.

-

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

How long did Residential Institutions exist?

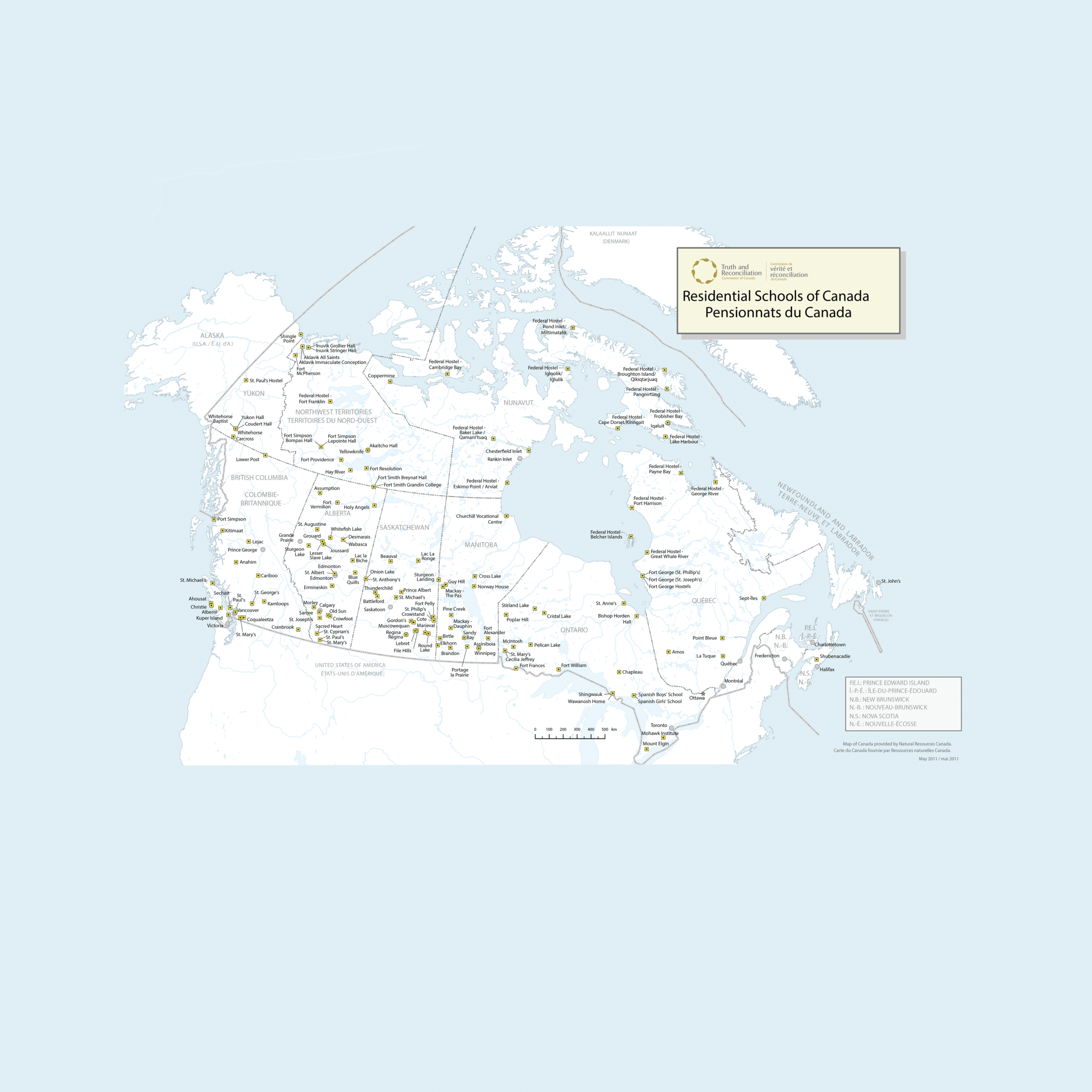

From their start in the 1800s until the last one closed in 1996, about 130 Residential Institutions operated in every province and territory in Canada, except for the provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. During this period, over 150,000 Indigenous youth were enrolled in Residential Institutions. Enrollment reached a peak about 1930, with over 17,000 students in 80 Institutions. As of 2012, about 93,000 Indigenous adults who attended Residential Institutions were still alive to tell their stories and describe their experiences.

A number of factors laid the foundation for the creation of Residential Institutions:

Racism and Superiority

The dominant European mentality and view of Canada’s original inhabitants was racist and backwards. The Government of Canada considered it necessary to “assimilate” Indigenous Peoples, and to have Indigenous nations conform to the European/Canadian customs, attitudes and ways of dressing, believing, behaving and working. Some politicians (and others) of the time sought to “kill the Indian in the child” and “civilize” Indigenous youth by separating them from their heritage and customs and indoctrinating them to European and Christian ways. This false, misguided and racist perspective denied and rejected the validity of First Nations languages, customs, spirituality and traditions. The main reason for these assimilationist policies was for land and resource exploitation. Dispossession and extinguishment of rights would also help to ensure the establishment of Canada as a legitimate nation state.

Indian Act, 1867

In 1876, the Government of Canada introduced the Indian Act. Under the Act, the Government of Canada took control of all aspects of the lives of First Nations Peoples, including their means of governing themselves, their economies, religions, customs, traditions, land use and education. The Indian Act includes criteria and a definition of who is an “Indian.”

Dismissal of First Nations Education Priorities

First Nations leaders supported education of their young. They recognized that providing their youth with the skills and knowledge relevant to the times would be important in the adaptation of their Nations and communities to the new situations arising from the presence of European settlers. However, the idea of separating children from their communities to attend school was not supported by parents and Elders.

First Nation leaders always insisted that schooling should be within, not distant from, their communities.

Failure to Meet the Spirit and Intention of Treaty Obligations

Treaties with First Nations obligated the Government of Canada to fund the education of First Nations youth.

Residential Institutios were the Government of Canada’s way of meeting their treaty commitments to education.

Politics and Economic Expansion Plans for Canada

Indigenous Peoples were considered to be a “problem” because their presence was getting in the way of the continuous expansion of settlement and exploitation by the European powers. Assimilation and absorption of Indigenous Peoples into the “mainstream” were considered to help eliminate the “problem.”

Christianity

Christian missionaries considered it their duty to convert First Nations to what they considered to be the only true religion, Christianity.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Map of Residential Institutions Recognized Under the IRSSA

139 Residential Institutions were recognized under the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA).

Over 1500 institutions were not recognized under the terms of this agreement. ALTERNATE MAP

Explore the map by touching the labels:

Section 2

Residential Institution Experiences

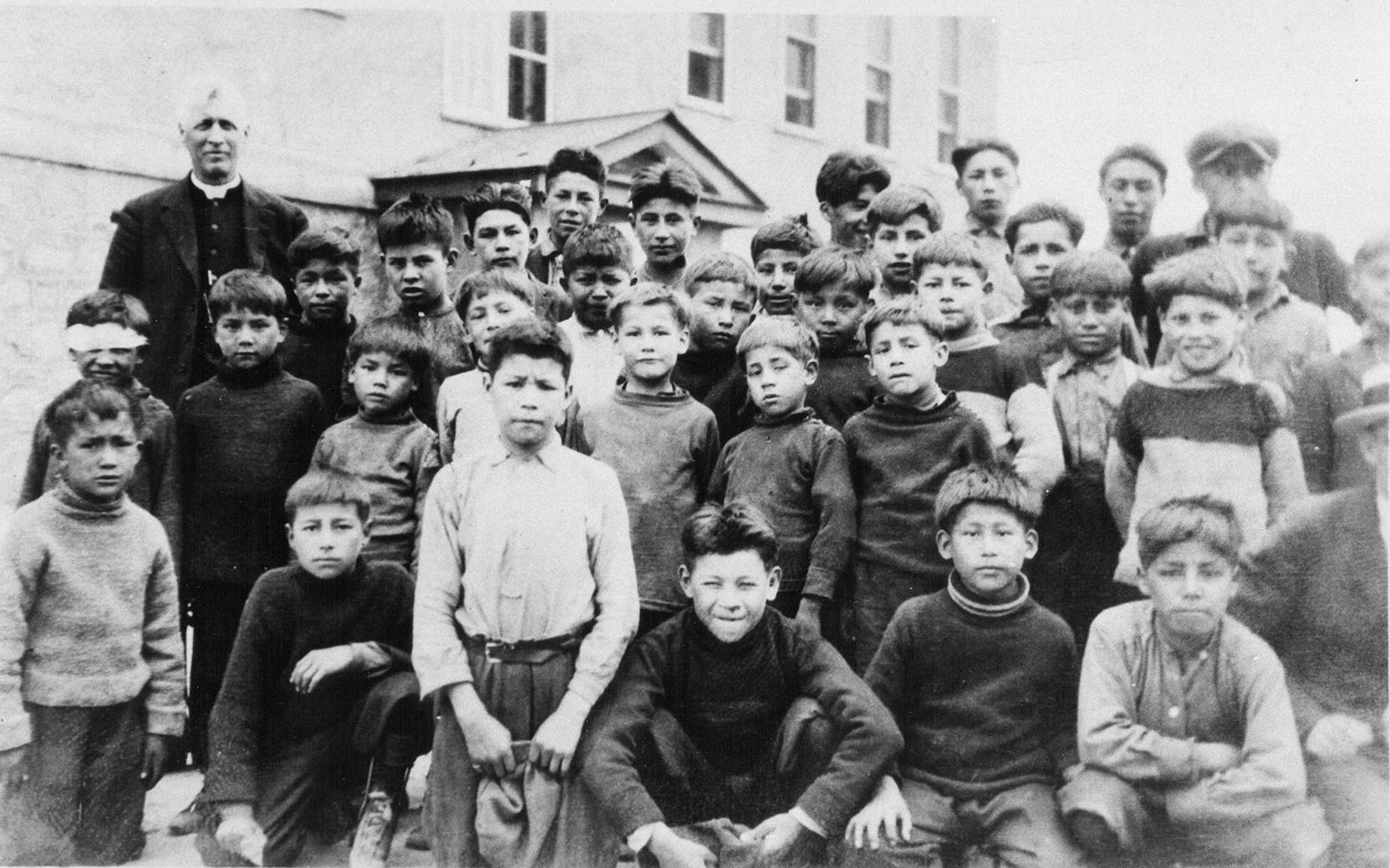

For almost their entire history, Residential Institutions were run by religious organizations—Christianity’s Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Methodist Churches. Their missionaries, ministers, priests and nuns administered the schools, taught the classes, and looked after the students all within a Christian framework. Many of these people were sincerely devoted to making a positive change in the lives of their students, although overwork, poor pay, isolation and colonial attitudes took their toll on the quality of education and on the well-being of the students. As part of the assimilation process, students were forbidden to respect or continue their First Nations customs, traditions and languages.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

The federal government provided most of the funding for Residential Institutions. However, as the system grew and expanded, there were continuing reductions, leading to severe underfunding for much of the time. From the beginning of the Residential Institution system, federal politicians were aware of the problems caused by inadequate funding and poor instruction, but such observations were suppressed and ignored.

Students typically attended these schools for 10 years or more. They were usually taken from their homes at five years of age, and generally finished school at age 15. Some students were able to go home for the summer, but it wasn’t uncommon for students to remain at Residential Institutions for the entire duration of their schooling years and not ever see or visit their parents and family members and community.

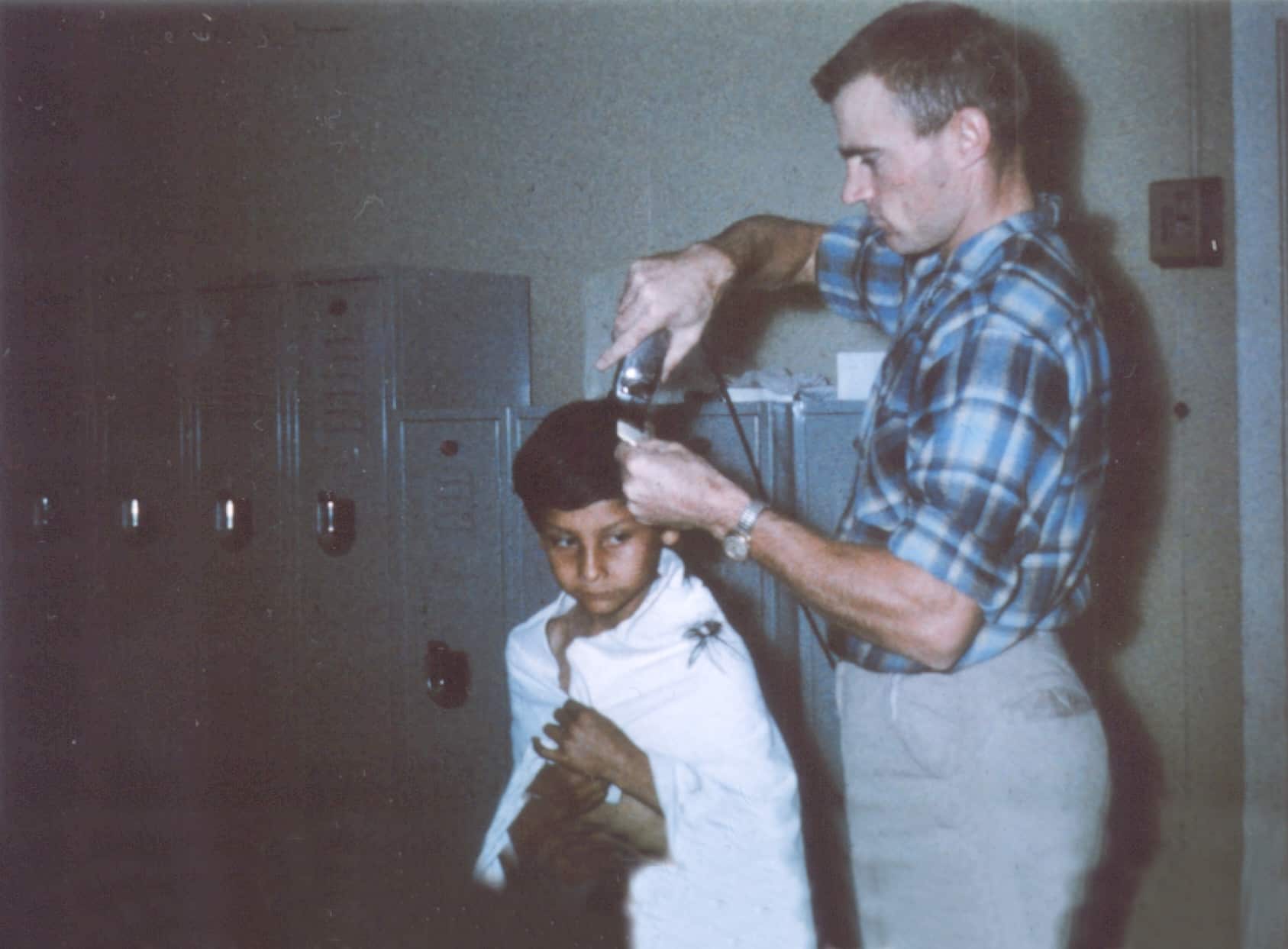

When youth arrived at their Residential Institution, they were stripped of their First Nations identity. Possessions and clothing were taken away. Youth were assigned uniforms. Their First Nations name was abandoned and replaced with a Christian name. While at the schools, students were deprived of their First Nations heritage—language, customs, and spirituality—without being provided with a sustainable and viable alternative.

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of one former student's story.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Some students had positive experiences and received decent educations. However, many students were subjected to or witnessed a wide range of indignities, including humiliation and nutritional, physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. In addition, because visits by family and community members were rare and often forbidden or impossible, students experienced feelings of loneliness and isolation. Not surprisingly, students were susceptible to disease and poor health. Suicide was not uncommon.

To reduce costs of operation, some Residential Institutions exploited the students by requiring that the students work for half the day, thereby limiting the time available for education. Funding limitations also affected the quality of education. Many of the teachers at Residential Institutions were not properly trained, lacking professional certification and qualifications. Poor housing conditions caused by inadequate funding adversely affected student safety and well-being. It is estimated that up to 50% of students who attended Residential Institutions died there!

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

How did Residential Institution students fare as adults?

Residential Institutions were created and designed to prevent students from acquiring the skills, knowledge, attitudes and understandings of their First Nations culture. First Nations youth attending Residential Institutions were deprived of their families, communities, and heritage. The Residential Institution experience prevented students from learning the traditional ways and patterns of their culture—the customs, stories, ideas, language, spirituality, ethics, morality, language, etc. The Indian Act compounded these losses by declaring it illegal for First Nations to take part in sacred ceremonies like the Potlatch and Sun Dance. Added to the cultural interference was the humiliation, deprivation and abuse many First Nations youth encountered in Residential Institutions. Many students who had attended Residential Institutions subsequently had profound identity problems, confused about who they were and their place in their First Nations culture and in the wider Canadian culture.

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of his story.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

How did Residential Institutions affect others?

Residential Institution experiences have had profound effects on other members of First Nations communities. These effects have come to be known as the “intergenerational legacy” of the Residential Institution system, influences that have been passed on from generation to generation. This intergenerational legacy has been described as the “effects of physical and sexual abuse that were passed on to the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Indigenous people who attended the Residential Institution system.” From an Indigenous perspective, these effects are expressed in the mental, emotional, physical and spiritual dimensions of the Indigenous life experience.

“We were made to feel ashamed for having been born Indian.”

— Esther Love (Faries), Residential Institution Survivor

Negative impacts of Residential Institutions:

Source : FNIGC, First Nations Regional Health Survey, 2008/10

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

When did the general public learn about Residential Institutions and their problems?

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the general public became aware of how the events at Residential Institutions had impacted generations of First Nations communities. Although problems of disease, hunger, overcrowding, staff training, low quality of education and building disrepair had been pointed out long ago, little or nothing had been done for decades.

Former students of Residential Institutions, who came to be known as “Survivors” of Residential Institutions, reported their own experiences. Finally the media and politicians paid attention. A period of lawsuits and hearings resulted in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. In addition to providing financial compensation to Residential Institution Survivors, the Agreement established the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission to document the real events at Residential Institutions and make that information available to all Canadians. The Commission’s purpose was to “guide and inspire First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples and Canadians in a process of truth and healing leading toward reconciliation and renewed relationships based on mutual understanding and respect.”

Section 3

Public Response to Residential Institutions

Between 1986 and 2009, all of the Churches directly involved with the Residential Institution system made public apologies for the abuses, neglect and suffering the First Nations youth had experienced while under their care. Churches began to work with their congregations to address this issue and to work towards reconciliation.

“Grandson, they are beginning to see us.”

— Grandmother of the former National Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

How did the government react?

In June 2008, the Government of Canada formally apologized for the Residential Institution system and for the government’s role in isolating Indigenous children from their homes, families, and cultures. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper called Residential Institutions a sad chapter in Canadian history and that the policies that supported and protected the whole process were harmful and wrong.

Assembly of First Nations Response

Former National Chief Phil Fontaine issued a moving statement that honoured the many First Nations people who had suffered the consequences of the Residential Institution system, and reaffirmed the strength and survival of First Nations Peoples in Canada. The federal apology pointed the way to “a respectful and therefore liberating relationship between (First Nations people) and the rest of Canada.…We must capture a new spirit and vision to meet the challenges of the future.”

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

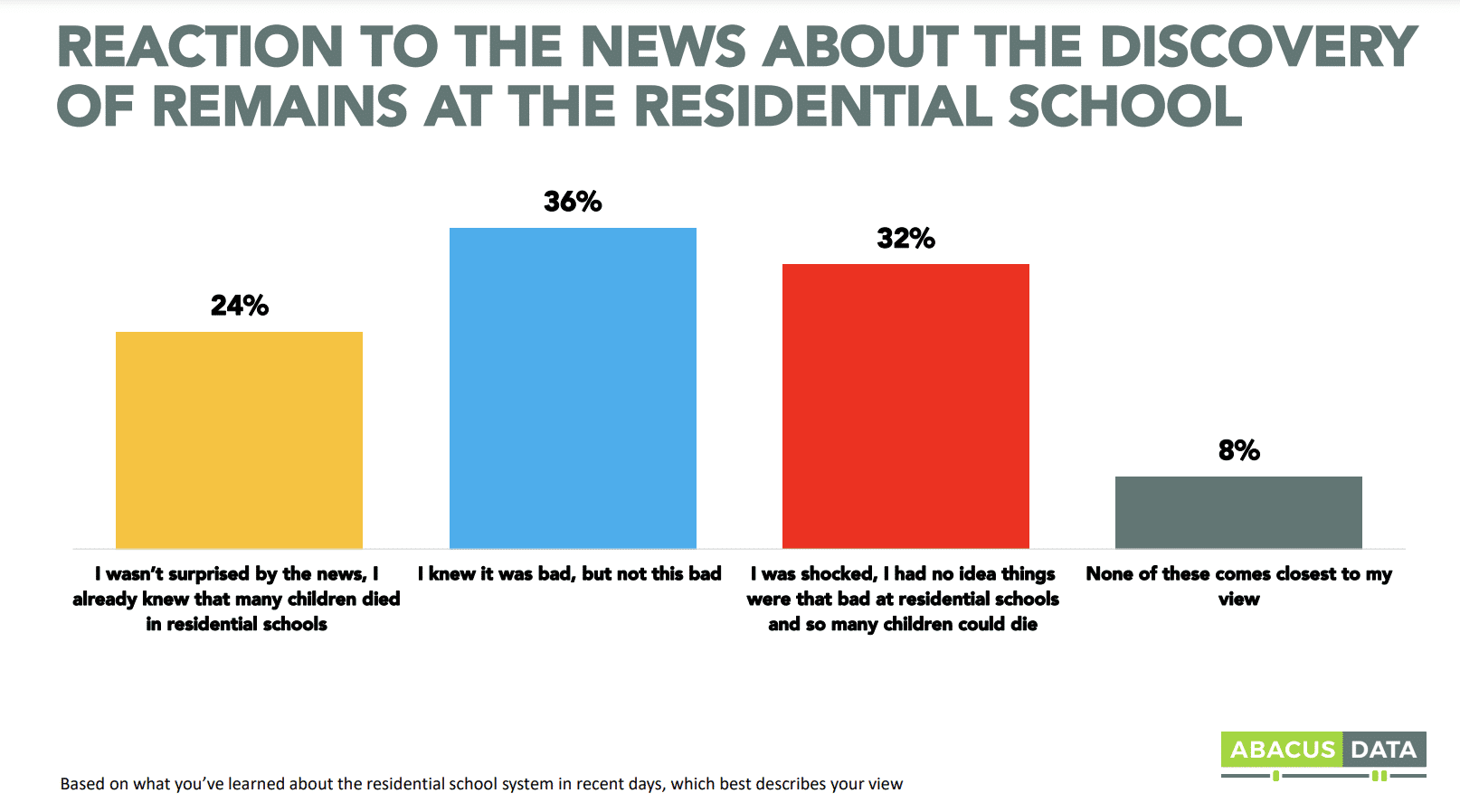

2021 Survey

The AFN and the Canadian Race Relations Foundation commissioned a survey that was conducted from June 4 to 8, 2021.

Key Highlights:

Only 34% of Canadians say they are very or quite familiar with the Residential Institution system.

6 in 10 have been following news of the discovery of remains at the Kamloops Residential School closely; 93% are aware of it.

4 in 5 expect there to be more gravesites found at Residential Institutions in the future.

62% of respondents said students in their province do not learn enough about what happened in Residential Institutions.

70% of respondents believe that schools in their province tend to play down or understate what happened at Residential Institutions.

58% agree that the Residential Institution policy and the way it was carried out was “genocide”.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

What Other Actions Have Been Taken

In 1972, Indian Control of Indian Education asserted the right of First Nations to control their own schooling. This document, updated in 2010 as First Nations Control of First Nations Education, laid out the values and principles underlying First Nations education and reinforced the importance of language and culture as the foundational elements to support student success. First Nations are working hard to overcome the legacy of Residential Institutions and have demonstrated many successes that attest to the spirit and resilience of First Nations people.

In 2010, the Canadian Senate adopted a motion to study and report on the progress made on the Government of Canada’s commitments since the apology to former students of Indian Residential Institutions.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Despite the legacy of Residential Institutions, First Nations are exerting control over their education now more than ever. As a result of First Nations advocacy, in 2019, the federal government replaced it’s outdated, inefficient, and inadequate proposal-based education programs with regional education approaches and funding models that provide more sufficient, predictable, and sustainable funding, completely reforming the way education is funded on reserve.

First Nations are now able to develop their own local, regional and/or Treaty based education agreements that identify the funding required to implement their vision of First Nations control over education. In 2022, nine REA’s have been signed and concluded, one is near completion, and 70 REA’s are underway. Read more in Book 11: First Nations Control of First Nations Education.

Section 4

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) overarching purposes are to reveal to Canadians the complex truth about the history and the ongoing legacy of the church-run Residential Institutions, in a manner that fully documents the individual and collective harms perpetrated against Indigenous Peoples, and honours the resiliency and courage of former students, their families, and communities; and guide and inspire a process of truth and healing, leading toward reconciliation within Indigenous families, and between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous communities, churches, governments, and Canadians generally.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission spent six years examining Canada’s Residential Institutions. Under the leadership of commissioners, the Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair, Dr. Marie Wilson, and Chief Wilton Littlechild, the TRC produced corroborating evidence of physical and sexual abuse, institutionalized child neglect, higher than normal mortality rates in schools, and horrific government-directed assimilation tactics. The report confirms much of what we already knew or suspected about the federal government’s apartheid-like assimilation policies and how they were driven by a European sense of racial superiority. The TRC’s work is critically important to ensure Canadians have a full understanding of their history.

Commission chair Justice Murray Sinclair said: “We must remember that at the same time that Indigenous children were made to feel inferior, generation after generation of non-Indigenous were exposed to the false belief that their cultures were superior. Imperialism, colonialism and a sense of cultural superiority linger on. The courts have agreed that these concepts are baseless and immoral in the face of inalienable human rights.”

Indigenous leaders greeted the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s summary report on Residential Institutions with openness while urging all Canadians to embrace the findings and close the gap.”

Mission Statement of the TRC

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission will reveal the complete story of Canada’s Residential Institution system, and lead the way to respect through reconciliation … for the child taken, for the parent left behind.

Vision Stattement

We will reveal the truth about Residential Institutions, and establish a renewed sense of Canada that is inclusive and respectful, and that enables reconciliation.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

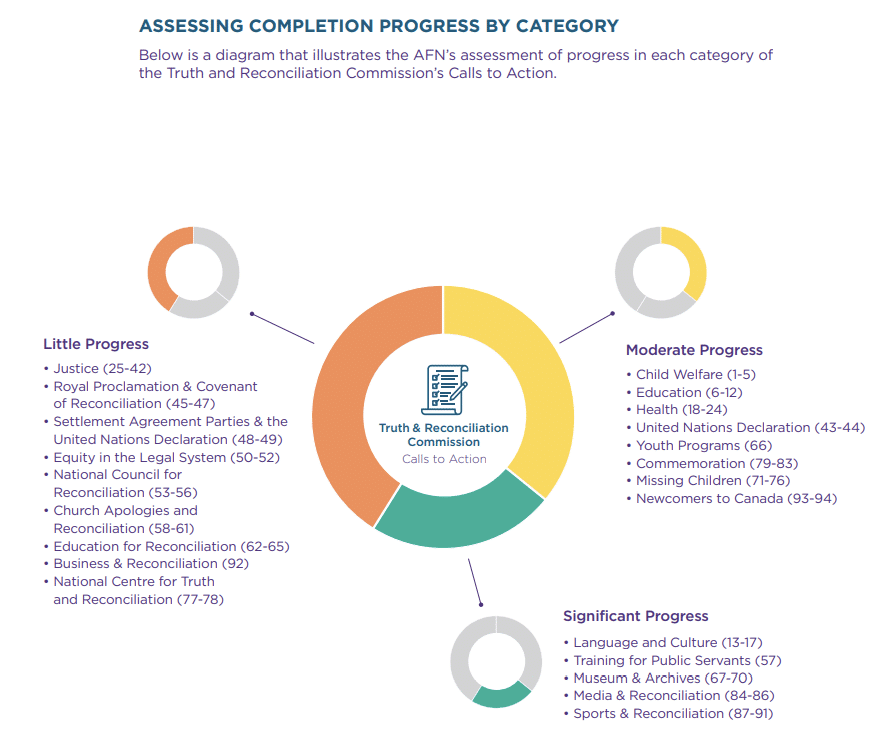

Calls to Action

In 2015, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared that his party would adopt and implement all 94 recommendations from the TRC’s report. Those recommendations, or Calls to Action, range from drafting new and revised legislation for education, child welfare and Indigenous languages to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and creating a national inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women.

Then-National Chief Bellegarde said that although all 94 recommendations are vital, addressing the education gap is one of the most important. One of the key recommendations in the report is that the history of Indigenous Peoples, the Residential Institution system and its legacy become part of the curriculum, from kindergarten to the end of high school.

Drawing from the strength of survivors, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has put Canada and Indigenous people on a path towards reconciliation.

“All Canadians are affected by the impacts of the Indian Residential Schools system and it is time to commit ourselves to reconciliation and action.

The impacts of Residential Schools are still with us and are contributing to the gap in the quality of life between First Nations and Canadians. We must close that gap.

The schools operated on the assumption that First Nations cultures and languages had to be eradicated and profoundly damaged the relationship between First Nations and Canada. We must repair that relationship.

Action is long overdue, and I believe that the Government of Canada must formally commit to working with First Nations and engaging Canadians in implementing the Commission’s calls to action.”

— Former AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde

Section 5

Unmarked Graves

Recoveries of unmarked graves have put a spotlight on the genocide committed through the Residential Institution system in Canada from the 1800s until the 1990s. As First Nations from coast to coast to coast pursue searches of Residential Institutions and the number of recoveries grows, we must remember each number represents a loss – a child with a name, a family and a community coping with grief. This is our shared history.

“We need time to heal, and this country must stand by us.”

— Chief Cadmus Delorme, Cowessess First Nation

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

In May 2021, the remains of 215 children were found on the site of a former Residential Institution in Kamloops B.C. This number would grow as many First Nations from coast to coast pursue searches at former Residential Institutions for unmarked graves.

Cowessess First Nation discovered 751 unmarked graves at the site of a former Residential Institution.

Ways the AFN is Seeking Justice

The AFN’s advocacy and role in the class action lawsuit resulting in the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) and Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), was the start to a greater understanding of the intergenerational trauma inflicted by Residential Institutions.

The AFN continues to press for accountability and meaningful action to help bring justice to First Nations. This includes continuing to urge the implementation of all TRC Calls to Action, advocating for investigations of former sites of residential institutions, accountability for crimes committed and an apology by the head of the Catholic Church in Canada.

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

TRC Calls to Action

The AFN continues to press for action, mandated by Resolution 15/01 Support for the Full Implementation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action.

Independent Investigation

AFN National Chief RoseAnne Archibald is calling for a United Nations (UN) Human Rights Commission Special Rapporteur to investigate the crimes and human rights violations associated with residential institutions.

Justice Minister David Lametti announced the appointment of Kimberly Murray to the role of Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Institutions to identify needed measures and recommend a new federal framework to ensure the respectful and culturally appropriate treatment of unmarked graves and burial sites of children at former Residential Institutions.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Calí Tzay has told media he will come to Canada to examine the “overall human rights situation” but stated that he does not have the authority to conduct an investigation or criminal prosecution.

Independent Investigation

“I am honoured to have been entrusted with this important responsibility of being the Special Interlocutor. I am committed to supporting the work of Survivors and Indigenous communities to protect, locate, identify, repatriate, and commemorate the children who died while being forced to attend Indian Residential Schools. I pledge to do this work using my heart and my mind in a way that honours the memories of the children who never made it home.”

— Kimberly Murray, BA, LL.B, IPC, Independent Special Interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian Residential Schools

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

International Criminal Court

The AFN has asked the International Criminal Court to investigate and hold the Imperial Crown, Government of Canada and the Roman Catholic Church accountable for their actions and to seek justice for the crimes against humanity for the victims’ families and the international community.

Roman Catholic Church

His Holiness Pope Francis visited Canada from July 24 to 29, 2022 and delivered penitential speeches to Indigenous peoples. He stopped short of denouncing the church’s role in creating systems that spiritually, culturally, emotionally and physically abused and killed First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children, as called for in Call to Action #58.

The AFN continues to focus its advocacy on the needs of Survivors and call for the Pope to rescind the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius, which seeded the genocidal process and included Residential Institutions.

The papal visit followed an AFN delegation which attended the Vatican March 28 to April 1, 2022. The Pope offered an apology to the full Indigenous delegation (First Nations, Inuit and Métis).

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Key Organizations Supporting Survivors

Indian Residential Schools Survivors Society

Indian Residential Schools Survivors Society is a B.C. based organization that’s been providing services like counselling and health and cultural services to Survivors of Residential Institutions. Residential Institution Survivors who need support can call the National Indian Residential School Crisis Line at: 1-866-925-4419.

Legacy of Hope Foundation

The Legacy of Hope Foundation’s goal is to educate and raise awareness about the impacts of Residential Institutions in the form of educational tools and consultation with Survivors.

Orange Shirt Society

The Orange Shirt Society works to raise awareness of intergenerational trauma caused by Residential Institutions and commemorate the experiences of Survivors.

First Nations Child and Family Caring Society

The First Nations Child and Family Caring Society develops education initiatives, public policy campaigns and provides resources to support First Nations communities and ensure the well-being of youth and their families.

Reconciliation Canada

Reconciliation Canada focuses on workshops and community outreach to further the dialogue around reconciliation.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation maintains a national database of records regarding the Residential Institution system and provides educational resources for Canadians to learn more about Residential Institutions across the country.

Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund

The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund works to provide education on the history of Indigenous Peoples and the legacy of Residential Institutions.

Tsow-Tun Le Lum Society

The Tsow-Tun Le Lum Society works with Residential Institution Survivors and provides outreach and cultural support. They also provide a toll-free line that Indigenous Peoples in crisis or needing support can call at: 1-888-403-3123.

Chapter 2Residential Institutions (Schools)

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

References

100 Years of Loss: The Residential School System in Canada.

AFN National Chief Calls on All Provinces and Territories to Commit to Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, Assembly of First Nations Press Release, May 31, 2016

AFN National Chief Phil Fontaine’s Response to the Statement of Apology, Assembly of First Nations, 2008, www.afn.ca

Residential Schools: The Intergenerational Impacts on Aboriginal Peoples. NSWJ-V7-art2-p33-62.PDF

http://zone.biblio.laurentian.ca

Saunders, Doug, Residential Schools, Reserves and Canada’s Crime Against Humanity, The Globe and Mail, June 5, 2015

Statement of apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100015644/1100100015649

The Healing Has Begun: An Operational Update from the Aboriginal Healing Foundation. May 2002. http://www.ahf.ca/publications/residential-school-resources

The Journey Ahead: report on progress since the government of Canada’s apology to former students of Indian residential schools.

They Came for the Children TRC INTERIM REPORT. ResSchoolHistory_2012_02_24_Webposting.pdf.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=4

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Residential Schools of Canada Map, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 2013

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Winnipeg, MB, 2012. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Wells, Robert, Wawahte: Indian Residential Schools, Trafford Publishing, 2012

Plain Talk 6 | Residential Institutions (Schools)

Wells, Robert, and San Filippo, John, Wawahte: Indian Residential Schools Documentary, 2012 www.wawahte.com

Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools. http://wherearethechildren.ca/en

AFN Response to Apology Statement. National Chief Phil Fontaine, Assembly of First Nations

Indian Residential Schools. Residential_Schoolshandout2.pdf www.afn.ca”

“Living a Life of Integrity Video

This AFN Youtube video supports the violence against women piece, role models, and residential schools: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9-

Prime Minister Harper offers full apology on behalf of Canadians for the Indian Residential Schools system.

Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools.

Smith, Joanna, Justice Murray Sinclair shares vision for Truth and Reconciliation, The Star.com, May 30, 2015